11001 A MONUMENTAL WALNUT, EBONISED DISPLAY CABINET MOUNTED WITH VICTORIA BAS-RELIEF WARE PLAQUES FOR THE 1878 PARIS EXPOSITION UNIVERSELLE DESIGNED BY CHARLES TOFT, WEDGWOOD & SONS English. Signed And Dated, 1878. Measurements: Height: 112″ (284 cm) Width: 73″ (185 cm) Depth: 35 1/2″ (90 cm)

Research

Of walnut with ebonized reeded moldings. Inset Wedgwood Victora bas-relief ware plaques on blue and green ground. The cabinet of angular projecting outline is surmounted by a gallery formed of Wedgwood foliated ballusters. The upper section with central glazed door enclosing reeded edged shelves of customized shapes. The side flanks divided by angular pilasters, enclosing shelved open continuous niches. The central oblique section with concealed drawer, the side returns of compliant shape. The conforming lower section with glazed central door and flanked by open shelved niches. The whole profusely mounted with Wedgwood panels of various shapes with subject matter including Hamlet, The Canterbury Tales, Othello, Paradise Lost and Comus. All raised on a plain plinth. The velvet lining probably original.

Marks:

Stamped twice to exterior:

Wedgwood & Sons. Manufacturers. Etruria.

Chas Toft. Sc. 1878.

Provenance:

Private Collection, Paris

This monumental cabinet bears the signature of Charles Toft (1832–1909), chief modeler at the Wedgwood ceramics manufactory from 1877 to 1888. It was the focal point of the company’s installation at the extraordinary Paris Exposition Universelle of 1878 and figure 1 shows a sketch in ink preserved at the Wedgwood Museum archives indicating how the piece was to be dressed for this event. Wedgwood enjoyed considerable success at the exhibition, reflected by the company being awarded a gold medal by the judges1 and the present cabinet was mentioned in a number of reviews of the exhibition, both in the Illustrated Guide to the British Section and the Reports of the United States Commissioners, with almost identical wording, as “a cabinet, decorated with jasper plaques, illustrative of Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Milton, modeled and designed by C. Toft.”2

An indication of the great effort and expense that went into the design and manufacture of this piece is the fact that the plaques and other porcelain elements had to be custom made: the plaques to the central section are tapered to match the angle of the drawer and the flanking side panels, and the balustrades that form the gallery were almost certainly made only for this piece. The foliate sectional panels that form the leading edge of the projections are so narrow that it seems likely they were also customized. Another interesting refinement is the design of the ebony and brass handles to the slanted drawer; these were specially constructed to restrict the range of their ball joints to avoid damage to the central plaque.

The piece incorporates Toft’s recently created range of plaques in “Victoria bas-relief ware” depicting subjects from English literature. The theme of this cabinet would have chimed perfectly with the taste of the period; the arches of the upper section are topped by bas-reliefs of leading figures from the canon of English literature. In the center is a bust of William Shakespeare (1564-1616), flanked by personifications of Fame. On the right-hand side is a profile of John Milton (1608-1674), on the left is one of Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343-1400).

Beneath each writer, on the upper face of the protruding lower tier, is a larger plaque showing a scene from his work. Beneath Shakespeare, as confirmed by the notes on the line drawing (see figure 1), is the famous “play within a play” scene in Hamlet. Toft’s work is notably similar to a picture of this scene painted by Daniel Maclise, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1842 (figure 2). It appears to show the near-identical composition, but from a different angle. This painting was engraved and distributed by the Art Union in 1868, and would have been a recognizable image amongst the contemporary public. Beneath Chaucer is the scene at the beginning of the Canterbury Tales when all of the protagonists from different sections of medieval society gather at the Tabard Inn in London prior to setting off on their pilgrimage. The tavern’s sign is clear to see in the upper right corner. Below Milton is a scene that is likely to be referring to his 1634 masque Comus, a tale of resilient virtuousness that was immensely popular during the Victorian period. It shows Sabrina rising from the water accompanied by water nymphs, a favored subject in contemporary painting; there are several works that may have been used as inspiration here, such as that by William Etty or perhaps William Edward Frost, which was, like the Maclise above, published by the London Art Union in 1849.3

The other figures shown on the rectangular plaques set vertically into the four columns are all taken from the works of these three writers, and some of them are instantly recognizable. We can see Adam and Eve from Milton’s Paradise Lost, Macbeth posed to strike with his two daggers, the Knight from Chaucer’s Knight’s Tale, one of the animal-headed torch-bearing revelers from Milton’s Comus and the figure resembling Bacchus is probably intended to represent Comus himself. Several of these figures are recorded in the Wedgwood factory pattern books, including Adam and Eve and one of the female characters who is identified therein as Emily from A Knight’s Tale (figure 3).

Some notable examples of pieces of furniture with integral Wedgwood plaques were created throughout the history of the factory’s existence, such as a cabinet made by Wright & Mansfield in 1867 for the Exposition Universelle in Paris, today in the Victoria and Albert Museum.4 However, these were usually designed and constructed by external makers and the present cabinet appears to be the only example of a piece of furniture designed by the Wedgwood company itself. Apart from its function as a vehicle for the display of Wedgwood’s collection, it is clear that Toft was hoping to demonstrate the versatility of these integral plaques, which could be sold individually for a range of uses; three of the same design as those on the cabinet are now in the collection of Manchester City Art Gallery,5 and some have appeared on the art market in recent decades.6

Toft cleverly combined Wedgwood’s traditional white-on-colored-ground stoneware techniques made using molds, with his specialist expertise in the newer pâte-sur-pâte decoration that was modeled and applied by hand with occasional additional slip decoration. This hybrid of techniques, demonstrated to great effect on the present piece, is referred to as “Victoria Bas-relief Ware.” It is likely that the company aimed to use the cabinet’s display at the exhibition to stimulate interest in mounting Wedgwood plaques on furniture; their London agent Charles Bachhoffner had complained in a letter to his employers in Staffordshire how the furniture in Paris showed “carved and paneled work is the vogue … it is very difficult to say in what direction to turn to regain the color plaque trade.”7

After the decline in popularity of the neoclassical style in the early nineteenth century consumers showed little interest in Wedgwood’s eighteenth-century staples of jasperware and black basalt, forcing the company to enter a difficult period of transition. However, fortunes began to revive in 1859 when Godfrey Wedgwood, great grandson of Josiah Wedgwood I, entered the leading partnership. Godfrey would run the business with his brothers Clement, Francis and Laurence throughout the later nineteenth century. This generation was considerably more dynamic than the previous, displaying a remarkable determination to make the company successful once more.

In 1875 a new London showroom was opened and the Staffordshire factory was modernized with the installation of ovens based on the models used by Minton.8 Godfrey also introduced modern artistic talent, such as Émile Aubert Lessore (1805-1876) who was employed as Lead Decorator in 1860. This French artist had studied under Louis Hersent and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres in Paris and had worked at the Sèvres factory from 1852 to 1858. He was allowed complete creative freedom, and oversaw the factory’s success at the London 1862 Exhibition. By the 1870s, both Minton and Wedgwood were racing to produce innovative wares to capture the burgeoning market for art ceramics with both firms investing heavily in design development. Minton established an art pottery studio in South Kensington in 1871, whilst Wedgwood set up a similar venture in Staffordshire. In 1875 Thomas Allen (1831-1915), widely recognized as one of the leading ceramicists of the nineteenth century, defected from Minton to Wedgwood to work as chief designer, leading the way for several other talented artists to make the move, not least Charles Toft.

Born in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, Toft was the son of an engraver and began his career as a modeler for Minton in the 1850s and later studied at Stoke Art School from 1860-64. He taught his craft at Birmingham School of Art between 1868-1873 and was appointed chief modeler at Wedgwood in 1877.

Allen and Toft first brought the themes of popular literature to the output of the firm in a fashion perfectly exemplified in the present piece. At the same time Frederick Rhead (1856-1933) also arrived at Wedgwood from Minton; both he and Toft had worked there under the notable ceramicist Marc-Louis Solon (1835-1913) the original great innovator of the new pâte-sur-pâte techniques, who had come to Staffordshire from Sèvres in 1870.9

The Paris Exposition Universelle, held from 1st May to 31st October 1878, designed by the French government to symbolize the country’s return to prosperity following the devastating Franco-Prussian war of 1870, was one of the most extraordinary and lavish world exhibitions of the nineteenth century. Attractions included the newly completed head of the Statue of Liberty, an extensive underground aquarium and an installation celebrating the French wine industry made from 75,000 bottles of champagne. The Exposition was enormous, covering 66 hectares, all of the area now occupied by the Eiffel Tower and the Champs de Mars.

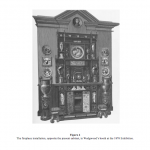

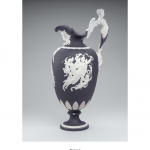

Given the high profile and immense scale of this event, considerable effort was applied by Wedgwood to ensure their display would be truly remarkable and it was in this context that the present piece was created. Descriptions give some idea of the overall composition of the Wedgwood exhibit: it seems that the cabinet was placed against a side-wall of the booth, opposite another elaborate installation in the form of a fireplace (figure 4).10 Both the chimneypiece and the cabinet were for sale, each for £300 retail or £250 wholesale.11 The above mentioned drawing (see figure 1) formed part of a “to do” list made in preparation for the exhibition containing notes about how the cabinet was to be dressed.12 The side cases of the upper level are annotated “horse vase;” most likely referring to versions of the company’s Pegasus Vase.13 Originally designed in 1786, the vase was decorated with scenes showing the Apotheosis of Homer and the Crowning of Virgil, ideal subjects for a literary-themed cabinet. The side cases of the lower tier are annotated on the left “war and ped” and on the right “peace and ped” possibly referring to a model of Toft’s own War and Peace vase, to be shown from its two different angles on pedestals. An example of this vase remains in the collection of the National Museum of Victoria in Australia (figure 5). In the center cases are sketches outlining the shapes of pieces to fill those spaces; the plan for the upper central case appears to have changed.

Toft was employed at Wedgwood until 1888, when he left to work as an independent designer. The decorative plaques on this piece, with their surprisingly modern styling, demonstrate the skill of this remarkable modeler, as well as the compelling prominence of historic literature in the Victorian psyche, while the cabinet’s monumental bearing reminds us of the wondrous age of the great exhibitions, a setting of ambition and optimism on a scale almost unimaginable to us today.

Considering the cabinet was made at the height of the florid and fanciful Victorian era, its singular appearance is a remarkable exercise in bold rectilinear design, eschewing any use of inlay, carved ornament, or shaped surfaces. Its dramatic angular, geometric form was clearly calculated to serve three functions; that of displaying Toft’s brilliant literary-themed plaques, to show off the free-standing Wedgwood objects inside, and as a tour de force that would earn admiration of informed visitors to the Exposition.

Footnotes:

1. Wedgwood Archive, Letters, memoranda, list and valuation of exhibits, Paris Exhibition 1878, List of Awards to Exhibitions, folio 29058-44.

2. Reports of the United States Commissioners to the Paris Universal Exposition, 1878. Published Under Direction of the Secretary of State by Authority of Congress, Volume 3, p. 132

3. See British Museum No. 1850,1109.264

4. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O21547/cabinet-crosse-mr/

5. Robin Reilly, Wedgwood Jasper, (London 1994) 267.

6. Christies Sale 7549, 19th Century Furniture, Sculpture Porcelain & Decorative Objects, 25 April 1994, New York, East, Lot 81

7. Wedgwood Archive, Bachhoffner Correspondence, June 1878, 28000A

8. Maureen Batkin, Wedgwood Ceramics 1846-1859, A New Appraisal, (London 1982) 14.

9. Batkin, op. cit., p. 61

10. Art Journal, Illustrated Catalogue of the Paris International Exhibition, XV, p. 215

11. Wedgwood Archive, Correspondence of Geoffrey Wedgwood from Paris in May 1878 to his brother Clement in Staffordshire.

12. Wedgwood Archive, Letters, memoranda, list and valuation of exhibits, Paris Exhibition 1878, folio 29058-44.

13. The British Museum, Inventory No. 1786,0527.1

Comments are closed.