11028 LITHOPHANE DEPICTING DRESDEN FROM BRUHL’S TERRACE BY THE MEISSEN PORCELAIN MANUFACTORY SET ON A NEO-ROCOCO GILT AND PATINATED BRONZE CANDLESTAND German. Second Quarter Of The Nineteenth Century. Measurements: Height: 23″ (58.4 cm) Width: 8 4/5″ (22.5 cm) Depth: 5″ (12.7 cm)

Research

The rectangular porcelain plaque cast with a view of Dresden mounted in a gilt- bronze frame surmounted by putti on neo-rococo stand with a two-light adjustable candlestick.

Marks:

Hand-incised on the back lower left corner:

118

Provenance:

Private Collection Massachussetts

Developed in Europe in the early nineteenth century, lithophanes are porcelain plaques cast with a design that, when back-lit, gives the appearance of being painted en grisaille. The name lithophane derives from the Greek lithos, meaning “stone,” and phainen, meaning “to cause to appear.” They were created by translating an engraving into a three-dimensional wax model, which was carved against a back-lit glass panel. A plaster mold was then made from the wax model and, finally, a porcelain plaque was created from the plaster mold, with low relief on the front and a smooth, flat back. The gradations of light and shadow depend on the thickness of the porcelain; where it is thinner, the lithophane appears brighter, whereas thick sections are more difficult to penetrate with light, and result in darker areas. The finished product was entirely made of porcelain, but when backlit was “as detailed and beautiful as any mezzotint.”1

Lithophanes were produced mainly in factory settings by skilled craftsmen using precision hand tools. Carving a model in wax could take anywhere from a few weeks to several months, depending on the size and complexity of the design. The works of art reproduced on lithophanes were derived from paintings and engravings familiar to nineteenth century consumers, including old masters, genre paintings and scenes of idealized family life, portraits, historical figures, scenes from popular literature, religious and biblical stories, hunting and battle scenes, and vedute, or scenes of well-known places in Europe.

The original patent for a lithophane, dated 1827, was registered in France by Baron Paul Charles Amable de Bourgoing (1791-1864). De Bourgoing came from a family of diplomats and he himself participated in various Russian military campaigns, served as an ambassador in Madrid, Berlin and Vienna, and became a peer of France. In addition to his political pursuits, the Baron was also “a scholar and ardent researcher whose passion for discovery and testing in the industrial arts often deprived him of sleep.”2 De Bourgoing imparted his invention to his friend and colleague Alexandre Brongniart, the director of the Sèvres porcelain manufactory, and to Georg Friedrich Christoph Frick, director of the Königliche Porzellan-Manufactur (KPM) in Berlin some time between 1834 and 1843.

Although Germany was not the first known country to patent lithophanes, they had been the first to invent true hard-paste porcelain in Europe at Meissen, and “had the best knowledge to develop this art form to its fullest potential.”3 The French patent was licensed to Germany a year after its registration and production of lithophanes at the Meissen factory began in 1828. Detailed records at Meissen reveal that two individuals who were particularly engaged in the creation of lithophanes were “Georg Friedrich Kersting (1785-1847), [who] was the manager of the decorating department from 1818 to 1845 and was significantly involved in the production of lithophanes, as was Carl Gottfried Habenicht (active mid-nineteenth century), who as the head of the art department created 130 models.”4

Documentation shows that demand for lithophanes produced at Meissen peaked around 18405 and the company exhibited them at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London. Lithophanes saw a marked decline in popularity toward the end of the nineteenth century, with the increasing accessibility to electricity. Of the 220 lithophanes in production at Meissen, 30 percent were eliminated after 1851 and all were removed from their product listing after 1860. The present piece is a rare survival from this short period of production.

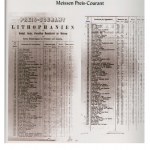

The present lithophane bears the number 118 on the back, which confirms it was indeed produced at the Meissen factory. This model number corresponds to Meissen’s Preis-Courant (pricelist) of circa 1846, where it is described as “Dresden von der Brühlschen Terrasse” (figure 1). The pricel ist records each model of lithophane available, the dimension of the piece, whether it was produced in white or also color (as some were painted), and the price for each in Prussian currency, Reichsthaler, Silber Groschen, and Pfennig. According to this pricelist, the present model was for sale at 19 Silber Groschen.

The view was taken from an engraving circa 1820 entitled Vue de Dresde, prise du jardin de Brühl (figure 2) by Christian Gottlob Hammer (1779-1864), “who is numbered amongst Dresden’s most important engravers of veduti.”6 He was said to have been greatly admired by J.W. von Goethe, who visited his studio in 1810, and was particularly known for his views of Saxony, Bohemia and Silesia. Amongst Hammer’s best works are those produced for the publishing firm Heinrich Rittner, in the volume “Dresden mit seinen Pachtgebäuden und schönsten Umgebungen” (“Dresden with her splendid buildings and most beautiful surroundings”).

Brühl’s Terrace is an architectural ensemble located above the river Elbe. Originally part of the city’s fortifications, it was given in 1737 to Count Heinrich von Brühl, Minister of Elector Frederick Augustus II, who built a palace with library, gallery and gardens on the site. Nicknamed the “Balcony of Europe,” the terrace was opened to the public in 1814. The view of the engraving looks west toward the Schlossplatz (castle square), centered by the Katholische Hofkirche, the Residenzschloss, and the Augustus Bridge.

The present lithophane is mounted in a candle shield, one of a variety of vehicles used to display these porcelain pictures. Candle shields protected the eye from the glare of bare flames while providing the viewer with an illuminated picture, which had the added charm of being almost animated by the flickering of the fire. “An interesting feature of some candle shields is the fact that many of the stands were devised so that the frame holding the lithophane could be raised and lowered with the height of the candle.”7 The present example is a variation of this model, with the candlestick being adjustable up and down along the stand. Its gilt and patinated bronze base and surround are of high quality and interesting design, a synthesis of elements derived from the rococo, classical and Renaissance canons. This eclectic combination chimes with the antiquarian taste of the second quarter of the nineteenth century.

Footnotes:

1. Carney, Margaret. Lithophanes. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Pub. Ltd, 2008. 7.

2. “Paul Charles De Bourgoing.” Base De Données Généalogique. N.p., 2011. Web. 17 Sept. 2013. <roglo.eu/roglo?lang=fr;m=NG;n=Paul+Charles+Amable+de+Bourgoing;t=PN>.

3. Carney, 20.

4. Ibid., 30.

5. Ibid., 29

6. Inter-Antiquariaat Mefferdt & De Jonge, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Dresden, original Aquatintaradierung – Hammer. http://www.inter-antiquariaat.nl//index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=0&products_id=5043

7. Carney, 120.

Comments are closed.