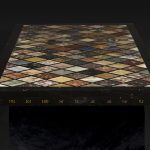

11046 A FINE MARBLE SPECIMEN TABLETOP, COMPLETE WITH ORIGINAL NUMBERING Rome. Late Eighteenth Century. Measurements: 2” (5 cm). 47” (120cm). 21” (54 cm).

Research

Rectangular, with a large range of lozenges with various specimens of marbles including rosso and nero antico, orange Veronese, yellow Siena, brown grey and white fleur de pecher, black and gold portor, orange and violet Spanish brocatello, and white Cararra, and hardstones including grey and red granite, red and white jasper, pink quartz, porphyry, bloodstone, serpentine, golden and brown agate, onyx and lapis lazuli. Set into a black marble ground. Restored edge. With complete engraved numbering, on one side; in6, in5, 101, 100, 76, 75, 15, 50, n6, n5.

Marble specimen tables of this kind became highly sought after in the later decades of the eighteenth century with connoisseurs keen to show off their knowledge, not only on classical sculpture and architecture, but also on the marbles and stones that were used therein. It was a fashion which naturally began in the 1760s in the epicenters of glyptic art, Rome and Florence, and which spread to other European centers including London and Paris. Eighteenth century geological collections would often include a number of plaques of fine stone removed from ancient ruins; the specimen table is in simply a more compact version of the same idea. In many ways such a table embodied Enlightenment-inspired enquiry, encouraged by geological pioneers like the Comte de Buffon (1707-1788), who had recently confirmed through the examination of rocks that the earth was much older than the five or so thousand years stipulated in the bible.

Like so many examples of this kind, the table would have likely been accompanied by a guide or key, which would explain what each sample was, and perhaps give examples of how they were used in practice. An example in the Victoria and Albert Museum, owned by three notable Englishmen, Dr. John Fothergill (1712-1780), Dr. J.C. Lettsom (1744-1815) and the architect George Gwilt (1775-1856), a noted Antiquarian and Historian, who worked on the restoration of Southwark Cathedral in the early 1820, is unusual in that it still retains its hand-written Italian key. That the present tabletop would have been used in this way is suggested further by the extraordinary survival of a rare engraved numbering system, which is still visible on one side.

Another example, this time made in England for Croome Court in Worcestershire is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Fig 1.). It incorporates a stand made by the premier English furniture manufacturer of the period, Mayhew and Ince, in 1794, hinting at the importance attached to such tabletops, which is further borne out by the fact that some collectors chose to be painted next to their specimen table, as in the case of The Marchesa Margherita Gentili Boccapaduli, who was painted by Laurent Pecheux in 1777 (Fig. 2).

Comments are closed.