11113 THE FORDE ABBEY COUCH OF STATE AN EXCEEDINGLY RARE CEREMONIAL COUCH WITH EMBOSSED LEATHER UPHOLSTERY AND POLYCHROME DECORATION English. Commonwealth Period (1649-1660). Measurements: Height: 42.3” (107.5 cm) Width: 94.4” (240 cm) Depth: 27.5” (70 cm)

Research

Of polychrome painted wood. Substructure consisting of six legs with turning, joined with stretchers, bearing elaborate original paint and giltwork on front and sides, with paint work of later date on back. Seat upholstered in stamped leather formed of three joined panels with brass studs, with evidence of original paint and gilding. Two flanking articulated ‘wings’ also upholstered in stamped leather with studs, supported by adjustable iron rods fitting into brackets, which also show evidence of gilding. Wood sections supporting the wings wrapped with further stamped leather and studs. Some minor damage to leather on underside of proper right wing. Two of the iron stays old but not original.

Provenance:

Probably made for Edmond Prideaux for use at Forde Abbey in the 1650s

Thence descent to Sir Francis Gwyn, 1702

House and contents sold to a Mr. Miles, 1846

Sold to Mrs. Bertram Evans, 1863

Thence by descent to Freeman and Elizabeth Roper, 1905

Remained at Forde Abbey until at least 1909.

Illustrated:

-Frederick S Robinson, English Furniture, London 1900, plate LXXL

-Herbert Cescinsky, The Old World House, London, 1924, p. 180

-Peter Thornton, Canopies, Couches and Chairs of State, Apollo Magazine, October 1974, p. 293

-Peter Thornton, Seventeenth Century Interior Decoration in England, France and Holland, New Haven and London, 1978, p. 173

Exhibited:

Bethnal Green Museum, 1896

Published & Recorded:

-FH Tomlinson, A Visit to Ford Abbey, London 1825, p. 16

-Unknown Author, A History of Forde Abbey Dorsetshire, London 1846, p. 83

-Forde Abbey Sale, Messrs. English and Sons, October 26-November 2, 1846

–Catalogue of the…Entire Effects of Ford Abbey; Presenting a Large Assemblage of Ancient and Modern Furniture…Sold by Auction By Messrs. English and Son…On the Premises, on Monday October 26th, and Seven following days of business, at 12 o’clock precisely.

-J.H. Pollen, Special Loan Collection of English Furniture and Figured Silks, Manufactured in the 17th and 18th Centuries. Held at the Bethnal Green Museum, London, 1896, no. 51

-Country Life, Forde Abbey Dorsetshire – part II, July 10th 1909, p. 60

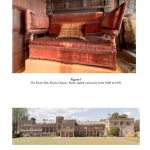

This piece must be considered one of the rarest intact survivals of mid-seventeenth century English furniture produced during the Commonwealth (1649-60). It is comparable to the so-called “Knole Sofa” from Knole House in Kent (figure 1), which occupies an iconic position in the history of the development of seat furniture.1 Through technical evaluation it has been evinced that both its painted legs and stretcher are original.

It is a testament to the couch’s historic importance that it formed part of numerous publications in the 19th and 20th century on the history of furniture. Evidence suggests that it was part of a set with accompanying chairs, made in the 1650s for one of England’s most picturesque country houses, Forde Abbey in Dorset, when in the ownership of one of Oliver Cromwell’s most senior officials, Edmond Prideaux (1634-1702). At that moment seat furniture of this kind was at its height of fashion; aspects of its design and decoration, such as the turning of the legs, painted detailing and gilded leather upholstery, are highly typical of its period, although only a handful of intact specimens survive. When new, the leather upholstery would have appeared richly colored, defined and glittering with vivid red, green, white and gold; the painted decoration on the wooden framework also included gilding, with a color scheme that matched the leather; even the metal brackets show evidence of gilding. It is a charming conceit of the piece that purpose-made embossed tassles are drawn along all the vertical surfaces of the leather to give the impression of fringing. It is clear that that this was a piece of furniture that was not merely designed for comfort, but was intended to impress, as in the mid-seventeenth century such couches had much more symbolic importance than we might imagine today.

The present couch is mentioned repeatedly in early nineteenth century accounts of Forde Abbey. In 1825 the local author F.H. Tomlinson was rather overzealous in his dating of it and the accompanying chairs; “We are now in the nineteenth century but the chairs around us graced this hall before the Dissolution:[2] they are very curious not only in regard to their form but also as to manufacture and are covered with leather, we need not say durable, gilt and silvered to curious patterns, the Sofa matches with them.”3 In 1846 an unknown author described how, “The ceilings are flattened, of beautifully carved wainscot, painted and gilt, with gold stars in the compartments. The walls are partly wainscoted with oak benches running around them. Some very quaint painted gilt leather chairs, and a peculiarly old fashioned sofa, were its furniture.”4

Forde Abbey is to be found on the border between Dorset and Devon and is formed from “the remains of the most perfect monastery in England”(figure 2).5 The original Cistercian abbey was founded in the 1140s and lasted until the reformation of Henry VIII some four hundred years later. Thomas Chard, the last Abbot, made major architectural additions including the cloister, which became the chapel, and the undercroft.6 The abbey then underwent several changes of ownership until 1649 when it was acquired by Edmond Prideaux, Attorney General and Postmaster to the Lord Protector Cromwell, who was said to have employed the architect Inigo Jones (1573-1652) to enlarge and convert it into a grand and habitable residence. This was when many of the extraordinary interior decorative elements were added, including the plasterwork ceilings and complex wainscoting. Prideaux did well out of the Cromwellian regime, his positions as Attorney General and Postmaster made him supremely wealthy, at his height of influence earning £15,000 a year, an astronomical sum at the time.7

It is most likely that he commissioned the present couch, which in the seventeenth century would have been an impressive signifier of status. It would have likely been dressed with expensive cushions and presented beneath a grand canopy in the main room of the house, much as in the case of the famous example at Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire, drawn in the eighteenth century in situ (figure 3).

Such canopies appear frequently in the inventories of important houses in the seventeenth century, where they are referred to as a “Cloth of State.” It has been argued by furniture historians that canopy and couch arrangements like this were intended to evoke a much larger state bed, which was the principal symbol of majesty and importance during this period.

Seat furniture of any kind, but especially examples with high arms, became the reserve of the rich and were status symbols appearing in portraits, such as one of an unknown lady in a private collection (figure 4). It also appears in engravings of the period such as a print entitled The Sense of Taste by Edward Marmion, a series that dates from the Cromwellian Period, which shows two fashionable ladies seated on a comparable couch, eating delicious foods within an elaborate interior (figure 5). An intriguing document preserved in the national archives dating from September 1642 to December 1643 appears to show Edmond Prideaux organizing the confiscation of furniture belonging to leading absent Royalists such as the Duke of Lennox and the Earl of Portland, including items like a long footstool, one folding stool, one long cushion all of crimson velvet, six high back stools and one elbow chair. Perhaps this is a hint at of how interested Prideaux was in furnishings and how he understood the status attached to such objects.8

Historians had traditionally assumed that the years under Oliver Cromwell were drab and plain. However, recent research suggests that the Protectorate regime, and especially the inner court circle, was considerably more modish than had been thought.9 Some lavish interiors were executed during this period, including those at Forde Abbey, which fall into the same category as the Double Cube Room at Wilton House, one of the most stylistically complex schemes of the seventeenth century. There is also evidence of leading figures of the regime attempting to express the new republican age, and finding ways of reconciling the sober nature of the period whilst still retaining a degree of grandeur.10 This might be what we see in the choice on the present piece of upholstery in stamped leather, a luxurious and expensive option, but a departure from the more commonly found velvet and fringing on other examples.

Stamped leather of this kind was not uncommon in luxurious interiors of the mid-seventeenth century, however, generally it was used for wall hangings; its deployment as upholstery occurs more typically in the later decades of the century. Therefore, the present piece, dating from the 1650s, was at the vanguard of taste. The material was made from treated cowskin faced with tin foil, which was then pressed into carved wooden molds and stamped with the aim of creating a beguiling and varied effect when lit.11 As seen here, paints and varnishes would often be applied to impart a variety in color. There is little doubt that this was a material of great luxury, which would have also seemed exotic and rare; the material was first created by the Moorish peoples on the Iberian Peninsula, hence the French term Cuir de Cordoue which is still in use. However by the seventeenth century most of it was being produced in the Low Countries, especially in the cities of Mechelen and Amsterdam, although it was also made in smaller centers across Europe from Germany to Italy.

Excitingly, the couch also retains its original painted decoration. Extremely high class pieces of furniture such as this would often be painted in this fashion. Similar decoration appears on the suite of seat furniture that accompanies the Knole Sofa, which has been claimed to be “a legacy from the Italian craftsmen patronized by the Tudors.” A royal warrant of 1611 that shows that some seat furniture in the royal palaces had their frames “paynted and guilte by John de Creete the Seriaunte Paynter.”12

After Prideaux, ownership of Forde Abbey passed into the Gwyn family in 1702 ; the next notable owner being Sir Francis Gwyn who also maintained important positions of authority, as a young man he was Groom to the Bedchamber of James II and held senior governmental posts in later life. He was a passionate antiquarian and added to the collection of fine art objects including the famous Mortlake tapestries that are still to be found in the house.13

Jeremy Bentham, among the most revered English philosophers of the nineteenth century rented Forde Abbey between 1814 and 1816 from the Gwyn family, raising the very distinct possibility that he sat on the present piece. The philosopher described the house as “an odd and venerable place: a various mixture of antiquity of various ages with modern elegance.”14

The Gwyn family tenure of Forde Abbey came to an end in October 1846 and an auction of its contents was arranged. This included Lot 108, twelve antique square chairs, covered in stamped leather and Lot 109, a settee to match, with rising ends. It seems, however, that despite its inclusion in the auction the present piece did not leave the house; it is likely that, as was the case with the Mortlake Tapestries, it was selected by the new owner of the house, a Mr Miles, to be purchased so as to preserve part of the history of the house.15

The later owners of Forde Abbey, the Evans family, lent it to the Bethnal Green Museum, opened in 1872 as an outpost of what would become the Victoria and Albert Museum, that was designed to educate and enlighten the working classes of the East End of London. In the catalogue accompanying the exhibition the present piece was described as a “settee covered with embossed and painted leather with brass studs, folding ends with iron plates and rods to secure them, legs and straining rails painted and gilt, about 1600, lent by W. H. Evans Esquire Forde Abbey Dorset”.16 It was presented alongside pieces from the Wallace Collection, which were lent by Sir Richard Wallace to be displayed to the public for the first time whilst he renovated Hertford House for their permanent display. How the couch came to be selected for exhibition in the museum is a point of interest; it is perhaps not coincidental that Jeremy Bentham had his friends the Mill family visit him at Forde Abbey on several occasions; and that their son, the renowned Economist John Stuart Mill, was close to the Founder and first Director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Sir Henry Cole.

After this point the couch seems to have become something of an icon of English sixteenth century furniture, as it was reproduced in books on the history of furniture, such as Frederick S Robinson’s English Furniture, published in 1900, where he explains “the settee belonging to Miss Evans of Forde Abbey, is rather exceptional. It is covered in embossed and painted leather. There are two folding ends with iron plates, and rods to secure them. The legs and straining rails are painted and gilt. Judging from the turning of its legs and the general plainness, the date of this should be quite as early as 1660, to which period it was assigned in the Bethnal Green Exhibition.”17 It also makes an appearance in The Old World House by Herbert Cescinsky, of 1924 where he mentions “the double-ended settee from Forde Abbey which is the last illustration to this chapter, has a leather covering and also a padding of tow, the Cromwellian substitute for later horsehair.”18 More recently, the couch was illustrated in Peter Thornton’s groundbreaking 1978 publication Seventeenth Century Interior Decoration in England, France and Holland to illustrate an example of a ceremonial chair.19

The couch’s movements during the twentieth century are unclear. It was still at Forde Abbey in 1909, when a Country Life article of July 1909 mentions “in the dining room is placed a day-bed with Spanish leather with two lifting ends … the Charles II type of this furniture had only one end, but that of an earlier date at Hardwick has two ends, like the one at Forde, on which, tradition says, Cromwell once slept.”20 It is unlikely that we will be able to prove whether Cromwell did indeed sleep on this remarkable piece, however it is hoped that with its recent reappearance, it will regain its previously held position as a key example of mid seventeenth century furniture that has much to say about the symbolic importance of this very special type of seat.

Footnotes:

- See Christopher Rowell, ‘A Set of Early Seventeenth-century Crimson Velvet Seat Furniture at Knole: New Light on the ‘Knole Sofa’ in Furniture History, 2006, pp. 27-52

- The Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536-1541).

- FH Tomlinson, A Visit to Ford Abbey, London 1825, p. 16

- Unknown Author, A History of Forde Abbey Dorsetshire, London 1846, p. 83

- Signed M.A, A history of Ford abbey, Dorsetshire, London 1846, p. 1

- For more detailed information about the history of Forde Abbey see the recent article, John Goodall, “A Commonwealth Restoration”, Country Life April 18th 2012, pp. 86 to 89

- Peter Thornton, Canopies, Couches and Chairs of State, Apollo Magazine, October 1974, p. 293

- Ref state papers online.

- See Patrick Little, “Cromwell’s Gay Attire” in History Today, Volume 58, Issue 9, September 2008

- See Tim Mowl, Architecture without Kings: The Rise of Puritan Classicism under Cromwell, Manchester, 1995

- Peter Thornton, Seventeenth Century Interior Decoration in England, France and Holland, New Haven and London, 1978, p. 118

- Rowell, op. cit., p. 44

- Colin Brooks, ‘Gwyn, Francis (1648/9–1734)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- The Correspondence of Jeremy Bentham, London 1968- vol. viii, pp. 404-05

- Country Life, ibid, p. 89

- J.H. Pollen, Special Loan Collection of English Furniture and Figured Silks, Manufactured in the 17th and 18th Centuries. Held at the Bethnal Green Museum, London, 1896, no. 51

- Frederick S Robinson, English Furniture, London 1900, plate LXXL

- Herbert Cescinsky, The Old World House, London, 1924, p. 180

- Peter Thornton, Seventeenth Century Interior Decoration in England, France and Holland, New Haven and London, 1978, p. 173

- Country Life, Forde Abbey Dorsetshire – part II, July 10th 1909, p. 60

Comments are closed.