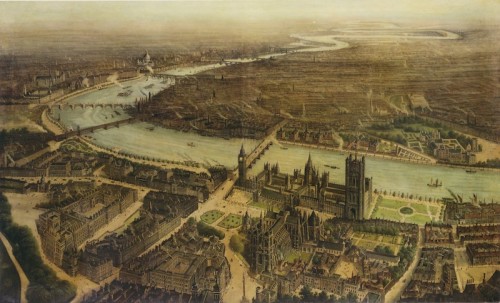

11167 PAIR OF PANORAMIC VIEWS OF WESTMINSTER BASED ON AERIAL STUDIES AND ENGRAVINGS BY HENRY WILLIAM BREWER (1836-1903) AND WILLIAM LIONEL WYLLIE (1851-1931) English. Circa 1895. Measurements Sight Size: Width: 98 5/8″ (250.5 cm) Height: 58 3/4″ (149.2 cm) Framed: Width: 113 3/4″ (288.9 cm) Height: 73 3/4″ (187.3 cm)

Research

Oil on canvas.

Provenance:

Julia Overing Beals, Massachusetts.

In the present pair of paintings, each depicts London from the same perspective view, however the scenes are separated by three hundred years. The first painting shows London in the late nineteenth century, the second revealing how the city would have appeared in 1584.1 The paintings are based on two engravings by the renowned English illustrators Henry William Brewer (1836-1903) and William Lionel Wyllie (1851-1931), which were published in May 1884 in the weekly illustrated magazine, The Graphic.

Henry William Brewer was an artist and member of the Royal Institute of British Architects, and was regarded as one of the most outstanding architectural illustrators of his day. His career began with a series of drawings of medieval buildings in Germany and from 1858 he became a frequent exhibitor at the Royal Academy.2 As well as his panoramas for The Graphic, Brewer was also renowned for his drawings of fantasy architecture together with his illustrations depicting buildings no longer in existence. He also produced a series of 16th century views of London, described as showing the city “in the time of Henry VIII,” from which one of the present paintings derives. A selection of these were published in The Builder after the artist’s death in 1903.3

William Lionel Wyllie was a prolific maritime artist and accomplished sailor. He studied at the Heatherly School of Fine Art and the Royal Academy School, during which time he won the prestigious Turner Gold medal for his painting Dawn After a Storm in 1869 at the age of 18. From the 1870s, Wyllie was employed by The Graphic as an artist of marine subjects. He was closely associated with the navy and, shortly before his death, at the age of 79, completed a large-scale panorama of the Battle of Trafalgar for the Portsmouth Dockyard, measuring 42 feet long and 12 feet tall. Upon his death, Wyllie was buried with full naval honors including a rowed procession up Portsmouth Harbor.

Brewer and Wyllie’s two views of London formed part of a long running series of panoramic cityscapes published by The Graphic in the 1870s and 1880s. Beginning in 1876 with Constantinople, the series also included Sydney, Cairo and Athens. Brewer, who specialized in aerial perspectives of cities, contributed views of Dublin and Rome as well as other British cites such as Liverpool, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Portsmouth, Oxford, Birmingham and Manchester.

The view depicting the city in 1884 was initially sketched by Wyllie, who accompanied Brewer during a balloon trip over the city and was taken from a point 1,400 feet above St. James’s. In his commentary on the view in The Graphic Brewer complained that “the rate at which the balloon passed over [made it] impossible to sketch sufficient detail.” Furthermore, Brewer added that “when looking down upon London from a great height the effect of the smoke is remarkable. Sudden gusts of wind carry it away from one point and pile it up in great columns over others… the rays of the sun also seem to pierce these great cumulus masses in the most strange and eccentric manner.”4 An engraving of a balloon trip over London by Wyllie published some years earlier in The Graphic (figure 1) gives an idea of the difficulties the artist would have faced in this precarious exercise.

Wyllie recounted how the feat was accomplished in a 1902 interview for Cassell’s Magazine: “It was a curious experience…We took our seats in the car and all we could see was the ring of dirty hands of the men who were holding us down. They were taken away, and in an instant, so it seemed, the men were out of sight and in their place below us appeared a wonderful panorama of London. I afterwards prepared a map ruled in squares, and sheets of drawing paper with the same squares drawn in perspective, on which I traced the river and buildings from the map. It was, of course, a difficult task to draw on wood afterwards—for that was before the days of ‘facsimile process’—as naturally everything had to be reversed.”5

Following the balloon flight, Brewer filled in the details of the engraving by visiting individual sites and viewing the city from various vantage points such as Victoria Tower. According to The Graphic Brewer’s wanderings did not go unnoticed: “While prying about for some architectural details, with a black bag, folding easel, and a map marked with suspicious red lines and crosses, Mr. Brewer was arrested as a possible Fenian [Irish Republican] terrorist outside the Houses of Parliament.”6

When it was published by The Graphic (figure 2), the 1884 view as described as “one of the largest wood-engravings ever issued by a newspaper.” The historic view (figure 3) was published in the same issue of The Graphic for comparative purposes, however, it was a much smaller engraving. Brewer wrote of this smaller, historic view that it was, “compiled from ancient maps and views of London, chiefly those by Agues, Norden, Hollar & c., compared with descriptions given by Stowe, Speed and other writers.”7

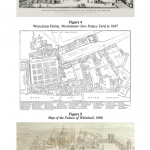

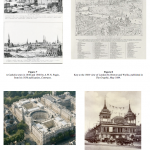

Brewer’s ancient views were conceived within the context of a revival of interest in antiquarian circles in the history of London, which took place during the 1880s. The Topographical Society of London was founded in 1880 and in 1881-2 the Society issued, as its first publication, a panoramic view of London by Dutch artist Anthonis van den Wyngaerde dating from 1544. Wyngaerde was one of the most important topographic artists of the sixteenth century, and it is likely that his view proved a valuable source for Brewer in his quest to record many of the buildings, by then disappeared, which make his historic view so fascinating. Also of undoubted importance to Brewer’s 1584 composition was the so-called Woodcut Map, the first “true map” of London as opposed to a panoramic view, thought to date from the 1560s.8 It was republished in 1874 with an introduction by the historian and Librarian W. H. Overall.9 Brewer’s rendering of the ancient palaces of Westminster and Whitehall are of particular interest. The former was something of a specialty subject of the artist’s; its defining features are clearly discernible, including Westminster Hall (the only part still extant) and the New Palace Yard, which also seems to rely on early seventeenth engravings by Wencelaus Hollar (1607-1677) (figure 4). Further to the left is Whitehall Palace, which was until its destruction by fire in 1698 the main English metropolitan royal residence. This rambling collection of buildings was at one time the largest palace complex in Europe; clearly distinguishable is the palace Privy Garden, laid out in a grid pattern, which was recorded on a plan of the 1680s (figure 5).

It is worth emphasizing that Brewer was not only responsible for preparing historic architectural illustrations for magazines such as The Graphic, but the lengthy, detailed and carefully researched accompanying texts, which clearly demonstrate the investigations he made in the process of preparing his drawings. Brewer was, like William Morris and John Ruskin, a founder member of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, an organization that would transform attitudes to the conservation and restoration of ancient buildings in Britain; it exists to this day and remains enormously influential. In The Graphic of 1877, Brewer himself wrote a lengthy explanation of why the new society was so crucial, outlining its aims in a cogent and persuasive fashion.10 It is clear he could take on the role of architectural activist, writing to newspapers to defend buildings, such as the Magdalene College Bridge in Oxford and the Organ Loft in Westminster Abbey.11 Expertise in the archaeology of parliament is discernible in his writings from 1880 when he published his first lengthy article on Parliament entitled Parliamentary Archaeology and Architecture.12 Examples of Brewer’s work remain in the parliamentary art collection, including a model based on his work, and a magnificent drawing, which is still frequently reproduced in books on the history of the Palace of Westminster (figure 6).13 In 1884 when the his aerial views were first published, a restoration of Westminster Hall, the only remaining part of the medieval palace that survived the fire of 1834, was taking place. The British Architect of 1885 tells us that Brewer was called upon to give his opinion to the parliamentary committee on the restoration, the report describing him as “the well-known architect”. Brewer was also a prolific artist, and could work effectively in watercolors. Paintings by his hand can be found in the British Royal Collection, of St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle and the Royal Mausoleum at Frogmore. In 1881 of a picture by Brewer of the Choir in Westminster Abbey was sold from the collection of the recently deceased Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881), the former Prime Minister.14 In Old London Illustrated, which was a compendium of Brewer’s drawings of London published in 1921 (nearly two decades after his death) it says in the foreword:

“For a quarter of a century, until his death in 1903, H. W. Brewer was one of the most valued and original contributors to both the artistic and literary departments of The Builder. For all his archaeological creations he spared no trouble in obtaining material…He was a devout member of the Roman Catholic Church, and to this fact, no doubt, may be traced his partiality for medieval buildings, especially those associated with religious orders. His retrospective powers will be evident to the most casual admirer of his works, and if the columns of the builder are searched, the results of Brewers labors recorded there will reward the diligent student.”15

It’s significant that Brewer was a Roman Catholic, as in this regard he can be seen as continuing the tradition established by Augustus Welby Pugin (1812-1852) who was also Catholic, worked largely Catholic patrons, and championed gothic architecture firmly within this context, hoping the architecture would encourage a return to a purer and more devout age. Indeed the format of the paintings is not dissimilar from the concept previously explored by Pugin in his polemic volume of 1836 entitled Contrasts: Or, a Parallel Between the Noble Edifices of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries and Similar Buildings of the Present Day, which argued in favor of the revival of Gothic architecture as a solution to contemporary flaws in both building design and social structure based on idealized medieval principals. Although he took a biased position, the book had a huge impact on 19th century architecture and design. Figure 7 illustrates a pair of plates in Pugin’s books depicting a Catholic town in 1440 contrasted with the same town in 1840 similar to that in the painting. That the Houses of Parliament were rebuilt in the Gothic style, rather than the more conventional neoclassical after the devastating fire of 1834 was largely owing to the campaigns of Pugin.

Accompanying the two engravings of London was a key to the 1884 view (figure 8) identifying 80 buildings together with a commentary on both illustrations by Brewer himself. Regarding the historic view, Brewer notes the old St. Paul’s Cathedral, which was destroyed in the fire of London, London Bridge covered with houses, and the vast open expanse of Lambeth marshes which by 1884 had long since been covered by the ever expanding metropolis. It seems that there may have been a time lapse between the London engravings and the present paintings as Tower Bridge, completed in 1894, appears on the painting but not in the engraving. Indeed the 1884 painting is a fascinating record of a largely lost London, on the cusp of the great Edwardian building boom at the turn of the twentieth century, which saw large swathes of the centre of the city such as the West End, Regent’s Street, Piccadilly Circus, Pall Mall and the Aldwych transformed. This was largely owing to the creation of the London County Council in 1889, which enabled the proper strategic planning of the city for the first time. The Council would occupy one of London’s most prominent riverside buildings, the County Hall, on a site in the center of the painting on the opposite side of the Thames from parliament, absent here because its construction only began in 1911. Interestingly, H.W. Brewer submitted a design for a new hall for the Council on Trafalgar Square in 1884. The monolithic Edwardian civil service complex, Government Offices Great George Street, based on Inigo Jones’s unrealized designs for Whitehall Palace, is also absent on the painting; it was begun in 1898 and not finished until 1917 when it became home to several government departments, most notably the Treasury in 1940 (figure 9). It is possible to see the ramshackle old Waterloo Station, the new Edwardian incarnation still in use today began construction in 1899. One of the most curious lost buildings included on the painting at the right center foreground was the Royal Aquarium and Winter Garden, recognizable by its distinctive twin towers, which existed between 1876 and 1903 (figure 10). This was intended as a multipurpose exhibition and entertainments space in the same vein as the Crystal Palace, and contained palm trees, fountains, sculpture, a theater at its west end, and most extraordinary of all, thirteen large tanks for sea creatures. It became especially famous for circus acts, boxing and other performances. The Methodist Central Hall was built on the site in 1905. On the south side of Waterloo Bridge is the Red Lion Brewery (figure 11), which was for decades a landmark of the south bank of the river until it was pulled down in 1949 to make way for the Royal Festival Hall; its famous lion was removed and reinstalled on the south side of Westminster Bridge. Other landmarks include St Thomas’s Hospital on the south bank of the Thames directly opposite Parliament, still on the same site but largely rebuilt, and the Royal Bethlam Hospital at St George’s Fields, now occupied by the Imperial War Museum. The famous Montague House, London home to the Duke of Buccleuch, is discernable along Whitehall (figure 12). This Victorian edifice replaced an earlier Georgian House in the 1850s, and was among the most glamorous London residences of the nineteenth century. It was taken over for use as government offices at the beginning of the twentieth century and eventually demolished to make way for the new Ministry of Defense in the 1930s. Westminster Hall is shown free of the Law Courts Building by Soane which encased it from 1822, to 1883. The courts moved to the new famous neo-Gothic buildings in the Strand designed by George Edmund Street, which are also clearly noticeable in the painting, behind Somerset House.

These paintings were formerly part of the collection of the Julia Overing Beals (1907-1997), descended from the Boit family, one of the most prominent and interesting Massachusetts families in the first half of the twentieth century. Mrs. Beals’ great uncle, Edward Darley Boit Jr., was an expatriate and artist who moved his family to Paris where he befriended the painter John Singer Sargent. Sargent’s famous group portrait, The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, now in the collection of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, immortalized his four girls, Mary Louisa, Florence, Jane, and Julia Overing Boit. The two large Chinese vases in the painting were inherited by Mrs. Beals before they too were donated by her daughters to the Boston MFA, where they now hang alongside the Sargent painting.

The question of how these paintings came to be in the collection of the family remains unanswered, however a close look at Julia Overing Beals’s family tree reveals a complex network that had much involvement in the architectural development of the city of Boston, especially in terms of the taste for the gothic style through their links with England. An important ancestor of Julia Beals was Russell Sturgis (1805-1887), a Boston merchant who worked in China, but eventually settled in London to become a Chairman of Barings Bank.16 His magnificently appointed houses in Cavendish Square and 17 Carlton House Terrace were popular society venues, where he hosted “a continuous complement of travelling Americans” including his nephew, Edward Darley Boit Jr. and the novelist Henry James.17 Russell’s son, John Hubbard Sturgis (1834-1888), was among the leading architects in Boston in the mid century and was the Vice President of the city’s Society of Architects.18 At the time few American architects travelled to Europe, but with his family connections, J. H. Sturgis was an exception to the rule, and has been described as an “architect, artist, anglophile and world traveler.”19 In 1859 he worked in the office of the important English Gothic architect James Kellaway Colling (1816-1905) learning a style that was “steeped in Ruskinian theory and well tutored in Reform Gothic foliate abstraction”20 In 1866 Sturgis formed a partnership with another important local architect, Charles Brigham (1841-1925) after which point he traveled almost annually to England, enabling his firm to keep abreast of the latest developments there. In 1876 Sturgis designed the original building of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in the gothic style, employing terracotta tiles in its decoration, in a fashion that drew inspiration from the London South Kensington Museum, the future Victoria and Albert Museum (figure 13). Many of the materials, including all the terracotta, were shipped from England with the assistance of Colling and Barings Bank. Sturgis maintained other successful partnerships with Boston architects such as Arthur Gilman (1821-1882) who was a friend of the architect of the Palace of Westminster, Sir Charles Barry,21 and G. J. F. Bryant. J. H. Sturgis’s nephew Richard Clipston Sturgis and other architects like Ralph Adam Cram (1863-1942) and H. H. Richardson continued the tradition of English-inspired gothic architecture in Boston into the later decades of the nineteenth century. Remarkably in 1875 there were plans to erect a church in the Brookline suburb of Boston based on the designs of Pugin himself and surviving photographs of the Banqueting Hall in the Salem residence of the great medical expert Francis Peabody, demonstrate the intensive nature of the gothic taste in the area at the time (figure 14). Julia Overing Blake’s maternal great grandfather, the railroad magnate H. Hollis Hunnewell built the Hunnewell Historic District, 17 miles west of Boston, where the aforementioned Arthur Gilman designed him a house on the estate; her grandfather Arthur Hunnewell had a house there by John Hubbard Sturgis called “The Oaks.”22 An uncle, James Frothingham Hunnewell (1832-1910), was a noted antiquarian who published books on English history and architecture, including perhaps his most famous effort The Imperial Island: England’s Chronicle in Stone of 1886.23

Boston was probably also the most receptive American city to the growing English arts and crafts movement, perhaps explaining why Morris and Company decided to present their first display in America at the Boston Foreign Fair of 1883. Eventually in 1897 the city established its own Society of Arts and Crafts, the first in America to do so. Charles Eliot Norton (1827-1908), the great art critic and writer, who had been a friend of Ruskin, Thomas Carlyle, Dante Gabriel Rosetti and Edward Burne Jones, was a major conduit of English influence into the city.24 It perhaps therefore unsurprising that the infamous English periodical of the 1890s, The Yellow Book, was published in both London and Boston. The Graphic containing Brewer’s drawings, and which enjoyed an excellent reputation in artistic circles, would have undoubtedly been extremely well received in the city too; two examples of Brewer’s work survive in the Boston Public Library.25

The Palace of Westminster, which is the central feature of both paintings, in its ancient medieval guise, and the more recent nineteenth century reincarnation, was the ultimate cause célèbre of the gothic revival movement. Given Boston’s love affair with English architecture and the gothic revival described above, it is not surprising that such paintings would have been owned by a Boston society figure, and especially a member of Julia Overing Beals’s internationally well-connected and architecturally-inclined family. However the exact story of their acquisition remains tantalizingly hidden for now.

Footnotes:

- The Graphic, May 31, 1884, London, pp 536-7.

- The Builder, 17 October, 1903, London, p 379.

- Ibid.

- The Graphic., p 530.

- Fish, Arthur. Mr. M. L. Wyllie, A.R.A. Cassell’s Magazine. Volume 24. London: Cassell, 1902. 255.

- The Graphic, p. 530.

- C. Wood, Victorian Painters, Woodbirdge, 1995.

- Original impressions of the ‘woodcut map’ survive at the London Metropolitan Archives, Magdalene College Cambrige and the National Archives Kew.

- Civitas Londinium. A Survey of London, Westminster and Southwark, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, 1874

- The Graphic, May 1877, Issue 389

- The Graphic, April 1873, Issue 178

- The Graphic, August 1881, Issue 612

- The model is mentioned in John Battley, A Visit to the Houses of Parliament, London 1947: “At the foot of the staircase leading to the Committee Rooms is a model of the Old Westminster Palace, after H. W. Brewer in the time of Henry VIII.” The drawing is Parliamentary collection WOA 82.

- The Evening Standard, July 16th, 1881, p. 2

- Old London illustrated; a series of drawings by the late H.W. Brewer, illustrating London in the XVIth century, with descriptive notes by Herbert A. Cox, London 1921

- Joan M. Marter, The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art, Vol. 1, New York, 2011, p. 602

- See Margaret Henderson-Floyd, “A Terra-Cotta Cornerstone for Copley Square, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 1870-1876 by Sturgis and Brigham”, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 32 No. 2, May, 1973;

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Paul Atterbury et al, AWN Pugin: Master of the Gothic Revival, London 1995, p. 206

- Annual Meeting Proceedings of the American Society of Landscape Architects, 1999, p. 218

- James Frothingham Hunnewell, The Imperial Island: England’s Chronicle in Stone, New York 1886

- Beverly Kay Brandt, The Craftman and the Critic, Defining Usefulness in and Beauty in Arts and Crafts-Era Boston, New York 2009, p. 89

- Boston Public Library, “G5784.D8A3 1890 .B7” and “G5774.E2A3 1886 .B7”

Comments are closed.