11201 CARTON FOR A TOILE DE JOUY PRINTED TEXTILE ENTITLED “LE PARC DU CHÂTEAU” BY JEAN-BAPTISTE HUET FOR THE OBERKAMPF FACTORY, DEPICTING THE FIRST BALLOON ASCENSION OF JACQUES A. C. CHARLES AND NICOLAS-LOUIS ROBERT French. Circa 1783. Measurements: Height: 26″ (66 cm); Width: 30 3/4″ (78 cm).

Research:

Ink and blue wash on paper.

Provenance:

Probably the Gaston and Albert Tissandier Collection

Collection of Paul Tissandier

William A.M. Burden, Jr.

Published:

LaVaulx, Henry C, Charles Dollfus, and Paul Tissandier. L’aéronautique Des Origines À 1922. Paris: Floury, 1922. No. 7.

This ballooning image, along with four others forming a group, represents a period in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century when all of Europe, and France in particular, became preoccupied with the hot air balloon experiments made by inventors and early aeronauts. Three of the present images capture the very first piloted flights in history, made within weeks of each other; with these liftoffs man’s greatest ambition and dream, which until that moment was simply unbelievable to most, were achieved.

They include the first manned hot air balloon flight of the Montgolfier brothers, flown by Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and the Marquis François Laurent le Vieux d’Arlandes on 21 November 1783; and the first manned hydrogen powered balloon flight made by Jacques A.C. Charles and Nicolas Robert on1 December 1783. It was for these aeronautic pioneers that hot air balloons became known as montgolfières and gas powered balloons were called charlières. The third image depicts a hot air balloon ascension made by Joseph Montgolfier and Pilâtre de Rozier on 19 January 1784. Other individuals were experimenting with the flight of lighter-than-air objects, but these men may be credited with setting the precedent for performing trials on a large-scale for the masses.

“These public tests aroused the curiosity and enthusiasm of the crowds who came to see the first liftoffs,”2 and accounts of the events were detailed in newspapers and engravings. Balloon imagery spread through all areas of the decorative arts; furniture and porcelain, clothing and accessories, wallpaper and upholstery, and the graphic arts were all influenced without exception. Particularly fashionable for reproduction were the iconic flights pioneered Charles and Robert, and the Montgolfier brothers.

“Savants and amateurs alike launched balloons into the air with great abandon much to the delight of the enormous audiences that gathered to watch and applaud their efforts.”1 One after another, new records were set in altitude, distance, duration and magnitude of the balloons, or as they were called, “aerostats.” While impressive, ballooning was also dangerous and a fair number of flights ended in disaster. However, the risks did not dispel the collective enthusiasm for this rather new science. The successes and dramas caused great fascination and many more experiments were carried out, including the remaining two flights illustrated in this collection: a flight orchestrated by Vicente Lunardi on 29 June 1795 and, finally, an ascension made as part of the coronation spectacle for Napoleon in December of 1804.

Many prints and engravings representing balloons and ascensions exist, but contemporary paintings from the 18th century are rare. The present collection of works (with the exception of one engraving) belongs to a small group of paintings outside of a museum collection recording the early history of aeronautics.

The present group has the distinction of a long and distinguished history of ownership. It was formerly part of the Tissandier family collection. Gaston Tissandier (1843-1899) was a balloonist, adventurer and science writer, while his brother Albert (1839-1906) was a balloonist and illustrator. They assembled a vast collection of technical images, portraits, views of ascensions, etc. spanning 1773-1910. Many of these pieces passed into the collection of Gaston’s son, Paul Tissandier (1881-1945), himself an aviator and collector. In the early 1920s Paul, along with the Comte Henry de la Vaulx (a balloonist, author, and founder of major French/international aeronautical associations) and Charles Dollfus (an aeronaut, historian, balloonist, and director of the Museum of Air, France) published a book on the history of air travel entitled L’áeronautique des origines à 1922 (Aeronautics from its origins to 1922), in which three of the present pieces are reproduced.3

From the Tissandier collection, the pictures were acquired by William A.M. Burden Jr. He was the son of Florence Adele Twombly and William A.M. Burden, and his grandparents were businessman Hamilton McKown Twombly and Florence Adele Vanderbilt, granddaughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt. Burden began collecting as a young man, taking a long ‘grand tour’ before his marriage to Margaret Livingston Partridge in 1931; afterward he and his wife traveled extensively. The couple had homes in Florida, Maine and New York State, and Manhattan, and enlisted the talents of mid-century architect Philip Johnson.

He began forming his collection of aeronautical memorabilia while still at Harvard in the 1920s. After graduating he became a financial analyst specializing in aviation securities, and founded his own investment company. He would later serve as Ambassador to Belgium from 1959-1961, as well as the president and longtime trustee of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. A large portion of his aeronautica collection was displayed in the Institute of the Aeronautical Sciences museum in the 1940s and 50s.

The present picture appears to be an original ink and blue wash carton (preparatory drawing) for a toile imprimée, or cotton textile print, entitled Le Parc du Château designed by Jean-Baptiste Huet (1745-1811). It depicts the first balloon flight made by the French aeronauts Jacques A.C. Charles and Nicolas Robert, and was designed for production by the Oberkampf textile factory at Jouy-en-Josas circa 1783.

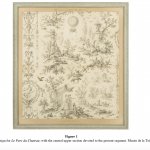

There exists in the Musée des Arts Decoratifs a very closely related design drawing by Huet on this theme, of which the present vignette only represents part; the full pattern for this toile incorporated further figural groups and arabesques along the left and right sides, which also included tiny balloons (figure 1).

The present carton concentrates on one section this larger design in which a finely dressed couple lingers in a garden setting between two fountains on the left, while on the right a shepherd plays his bagpipes amid his flock. The top central area is occupied by the balloon carrying Charles and Robert.

It has been pointed out by Esclarmonde Monteil, conservator and director of the Musée de la Toile de Jouy, that some of the toiles have a matching wallpaper produced by the Réveillon wallpaper manufactory. Huet also worked simultaneously for Réveillon, between 1775-1789, and it is possible that the present drawing represents a preliminary sketch for a wallpaper pattern rather than a textile. It is also interesting to note that the vignette is in reverse to the example of Huet’s full design for Oberkampf (see figure 1).

Printed cottons from India, called calicoes, were first imported to France in the late 16th century. They were light, colorful and easily washable, making them instantly successful and very much in demand. When the foreign product was in short supply, French versions called Indiennes, were produced. Concerned with the competition created for domestic textile industries such as silk and wool, the French government banned the importation of printed calicoes in 1686, followed by the prohibition of domestic production, wearing and use of the Indienne fabric in 1692. These laws proved impossible to enforce, however, and in 1758 the ban was lifted, resulting in the rapid establishment of manufactories to satisfy the demand for toiles peintes.

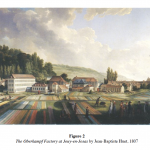

The most successful of these workshops was established by Christophe Philippe Oberkampf (1738-1815) in Jouy-en-Josas, near Versailles. Oberkampf was born into a German family of textile dyers. He learned the trade from his father, who established a mill for printed cotton in Aarau, Switzerland. At the age of eighteen he left home “to travel and work in other factories,”4 arriving first in Mulhouse, France in 1758 where he worked as an engraver for Koechlin-Schmaltzer et Cie. In that same year he returned home and was recruited by a dyer from the textile-printing factory of the Parisian banker-turned-industrialist Jacques-Daniel Cottin. Oberkampf worked as a colorist in Cottin’s textile factory for about a year before being offered the directorship of a brand new workshop set up by Antoine Guerne de Tavannes, a civil servant at the Contrôle Général des Finances. He accepted the job on the condition that the factory be built on a site selected by himself. Thus, the works were established along the Bièvre river in Jouy-en-Josas, (figure 2) and “on May 1, 1760 the first piece, designed, engraved, printed and dyed by Oberkampf was taken from the press.”5

The location of the factory was perfectly suited to the manufacturing process. The Bièvre river, “famous for the purity of its water, was ideal for the successive washing operations,” while the surrounding meadows allowed the fabrics to be laid out in the sun and bleached white.6 To produce printed designs on cotton, a mordant was first applied to the fabric which would bind the dye in whatever pattern it was applied. Mordants were ferrous or aluminum based compositions thickened with gum and, because they were colorless, were usually mixed with a Brazilwood decoction to give a faint color so that the printer could follow the design. Afterward, the fabric was submerged in a vat of dye, which would adhere only to the areas treated with the mordant; madder root-based dyes in varying concentrations would produce all shades of red, indigo and woad were used to produce blues, and weld resulted in yellow.

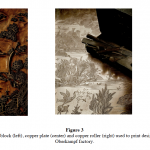

The mordants were applied to the cottons in one of three ways as the technology improved: woodblocks (used between 1760-1770), copper plates (used from 1770 onwards) and, finally, copper rollers. The first engraved copper rolling machine for textiles was invented in 1783 by Scottish inventor Thomas Bell, and Oberkampf was the first to put it to use in France in 1797. With this new development, it was possible to produce up to 5,000 meters of printed fabric in a day.7 Figure 3 shows an examples of a woodblock, copperplate, copper roller (one of only fourteen still preserved) that were used by the Jouy factory.

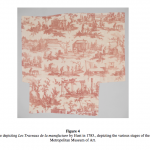

Oberkampf’s “genius and untiring energy elevated textile printing to a fine art and made it a leading industry in the land of his adoption,”8 and in 1783 the factory was awarded the title of Manufacture Royale. To commemorate this honor, and to celebrate the work and reputation of the factory, he commissioned a design representing Les Traveaux de la manufacture (figure 4), from the artist Jean-Baptiste Huet, marking the beginning of a long and prosperous partnership.

Huet was born in the Louvre on October 22, 1743 to a family of artists; his father, Nicolas Huet, was a painter in the Garde-Meuble du Roi and his uncle, Christopher Huet, was a professor at the Academy of Saint Luke. Because his father was a royal painter and the family lodged at the Louvre (which was then the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture), Jean-Baptiste was surrounded by artists like Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin and François Boucher, and he was apprenticed to the animal painter Charles Dagommer. He developed an interest in printmaking and around 1764 entered the atelier of Jean-Baptiste le Prince, a painter and etcher who had himself been a pupil of Boucher. Here Huet developed his skills as an engraver; most of his prints were of his own works. He was reçu by the Royal Academy in 1769 as an animal painter, and went on to achieve success with pastoral and genre scenes in the 1770s. His works reflected the influence of the Enlightenment philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau and an idealized view of nature, and “he arranged his scenes in a spacious, easy manner, creating designs of great airiness.”9

In the 1780s Huet began a move toward the decorative arts, in particular to textile design, providing cartons for tapestries to the Royal Beauvais Tapestry Manufactory. At that time it was headed by the artist Jean-Baptiste Oudry who, in collaboration with Boucher, saw the factory to its apogee in the 18th century. Huet designed a series of ten tapestries for Beauvais entitled Pastorales à Draperies Bleues et Arabesques. No fewer than three commissions for this set were executed, including an order made by John Campbell, 5th Duke of Argyll for his castle at Inverary, where they remain today. Aubusson, too, created tapestries based on engravings by Huet. As mentioned, he was also engaged by the wallpaper manufacturer Jean Baptiste Réveillon, who rose to prominence in the second half of the eighteenth century with papers based on neoclassical and arabesque designs, and those copied from ‘Indian cottons.’ Notably, Reveillon himself was involved in the history of ballooning in France; his manufactory produced the massive papers that decorated the envelope of a balloon launched in September of 1783 by the Montgolfier brothers on the grounds of his factory, Foile Titon, and at Versailles.

Jean Baptiste Huet’s most enduring position, however, was as chief designer for Oberkampf at Jouy-en-Jossas, from the time of his first commission from in 1783 until his death in 1811. It was “a most fruitful partnership, which contributed to the vitality and influence of the works,”10 as well as one of trust and confidence; it is known though the pair’s correspondence that Oberkampf gave a number of limited instructions to Huet, but generally left the artist free to choose his subjects.11

Huet’s works during his time at Jouy can be divided stylistically into three phases. The first style concentrated on pastoral and genre scenes of varying sizes placed on a plain background. In the second style, the same subjects continue but they are now accompanied by arabesques and foliated scrolls. The third phase of Huet’s work at Jouy was in marked contrast to the first two, ushered along by the events of the Revolution. Mythological, Medieval and classical subjects prevailed, and the backgrounds were filled in with geometric patterns.

The Oberkampf works initially concentrated on floral patterns for clothing before expanding to figural designs. “Soon turning to fashionable themes and recent events in the monochromes, however, Oberkampf spread the reputation of his factory’s products and assured its later fame…”12 These included rural, mythological, biblical, sporting, oriental, and topical scenes. The industry of printed fabrics capitalized on current political and cultural events that appealed to the broad public by incorporating them into textile designs, even appropriating popular images from newspapers and broadsides. Oberkampf was adept at selecting which images would be most appealing as well as the best time to introduce them to the market. He would also alter existing prints to keep up with the changing fashions, allowing pieces to remain saleable even after the original scene began to fall out of favor. As he noted:

One must be able to read into the future to know which type will supplant that which is already in place, because in every era, there is a type that is more sought after than the others and this will always be the case. The most skilled is also the man who knows when to stop in order to have the fewest leftovers when that type ceases to please.13

The design of the present carton is representative of the period in the late 18th century described as “balloon mania.” The Oberkampf factory produced at least three upholstery patterns with balloon motifs, but only two are known today.14 One of these, Le Parc du Château, numbered D108 by the factory and dating circa 1784, is illustrated in the present carton. It represents the ascent of Charles and Robert’s hydrogen balloon from the Tuileries Garden on December 1, 1783.

Between the months of June and December of that year, the Montgolfier brothers and the duo of Charles and Robert made alternating attempts at launching an aerostat; the Montgolfiers using fire, while Charles employed hydrogen. On November 21st the Montgolfier brothers launched the first manned hot air balloon from the Château de la Muette near the Bois de Boulogne, flown by the naturalist Pilatre de Rozier and the Count d’Arlanes. Just ten days later, Charles and Robert successfully piloted their hydrogen-powered balloon on the 1st of December.

Made of red and white striped silk, the envelope was covered with a varnish of rubber dissolved in turpentine to ensure its impermeability, but which also turned the white portions to a shade of yellow. The top half of the balloon was covered with netting, from which ropes were suspended and connected to a blue silk covered gondola, which hung below. They set the precedent of waving flags as they ascended above the cheering crowd, which can be seen here in Huet’s drawing and the numerous contemporary depictions of their flight. The pair reached an altitude of 2,000 feet and covered 27 miles before descending, at which point Robert disembarked. With the lightened basket, Charles threw out one of the sandbags and re-ascended, rising “to a height of nearly two miles as shown by the fall of [his] barometer”15 and traveling another 5 miles.

The present carton concentrates on one section of a larger design. In this segment, a finely dressed couple lingers in a garden setting between two fountains on the left, while on the right a shepherd plays his bagpipes amid his flock. The top central area is occupied by the balloon carrying Charles and Robert. Huet’s full pattern for this toile incorporated arabesques along the left and right sides, which also incorporate tiny balloons, and further figural groups below (figure 4).

The other known Oberkampf textile with balloon motif (for which the artist remains unknown) is again devoted to the exploits of Charles and Robert. Prior to their Tuileries flight, the pair experimented with a balloon that departed from the Champ du Mars on August 27, 1783. Upon arriving in the commune of Gonesse it fell, “to the great consternation of the peasants, who were unprepared for such an apparition, and attacked it as a creature of infernal origin. As they mangled it the sulphurous [sic] odor of impure hydrogen was enough to confirm their preliminary suspicions of its diabolic character.”16 The toile imprimée portrays this series of events with vignettes of the balloon’s lift-off, flight, and the ultimate attack on the balloon by peasants with muskets and pitchforks.

(Complete group of ballooning images comprises Carlton Hobbs Inventory Nos. 11201, 11202, 11203, 11204 and 11205.)

Footnotes:

- The Sublime Invention: Ballooning in Europe 1783-1820. Routledge, 2016.

- Gril-Mariotte, Aziza. “Topical Themes from the Oberkampf Textile Manufactory, Jouy-En-Josas, France, 1760 – 1821.” Studies in the Decorative Arts / the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design and Culture. (2009): 162-197. 165.

- LaVaulx, Henry C, Charles Dollfus, and Paul Tissandier. L’aéronautique Des Origines À 1922. Paris: Floury, 1922.

- Chapman, Stanley D, and Serge Chassagne. European Textile Printers in the Eighteenth Century: A Study of Peel and Oberkampf. London: Heinemann Educational, 1981. 115.

- Morris, Francis. “Romantic Period of Cotton Printing in France.” Needle and Bobbin Club. Bulletin, V. (1924). 34.

- Chapman, 18.

- Ibid., 28.

- Morris, 32.

- Riffel, Me élanie, Sophie Rouart, and Marc Walter. Toile De Jouy: Printed Textiles in the Classic French Style. London: Thames & Hudson, 2003. 42.

- Huet, Jean-Baptiste, and Benjamin Couilleaux. Jean-Baptiste Huet: Le Plaisir De La Nature. Paris: Paris Musees, Muse ée Cognacq-Jay, 2015. 137.

- Ibid.

- Gril-Mariotte, Aziza. “Topical Themes from the Oberkampf Textile Manufactory, Jouy-En-Josas, France, 1760 – 1821.” Studies in the Decorative Arts / the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design and Culture. (2009): 162-197. 163.

- Ibid., note 7.

- Ibid.

- Stevens, Professor W. Le Conte, “The History of Aeronautics.” Scientific American Supplement, No. 738, February 22, 1890, 11793.

- Ibid., 11792.

Comments are closed.