11474 A REMARKABLE MAHOGANY AND MAPLE WOOD NEOCLASSICAL CENTER TABLE WITH EBONIZED AND GILT-BRASS DETAILING AND NOIR BELGE TOP MODELED AFTER THE “TOMB OF AGRIPPA” Probably Eastern France. Circa 1800. Measurements: Height: 30 1/2″ (77.5 cm) Width: 30 1/2 ” (77.5 cm) Depth: 56″ (142.5 cm).

Research

Of mahogany, maple and ebonized wood, and gilt-brass. The rectangular noir belge slab top set on a rounded sarcophagus-shaped body with molded edge, the whole resting on two incurved trestle supports terminating in ebonized paw feet.

Marks:

Reverse side of the noir belge marble top inscribed, now partly illegible:

NT SEIGNR / ENT / ITE / RIERE. / MINÉ / MS. / CE MONUMENT

Provenance:

An old private collection belonging to a notable French publisher.

The present table was inspired by an ancient Roman porphyry sarcophagus known as the “Tomb of Agrippa.” Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (c. 64/62 BC–12 BC) was a Roman statesman and general who played an instrumental role in transforming the Roman Republic into the Principate by aiding Octavian, later known as Augustus, first emperor of the Roman Empire. As an architect, he was responsible for an impressive building program in the ancient city that included aqueducts, gardens, baths, and porticoes. Arguably the most notable contribution, however, was the building complex constructed on his own land in the Campus Martius, consisting of the Basilica of Neptune, the Baths of Agrippa and the Pantheon. Only the façade of the Pantheon’s original structure remains, with an inscribed dedication on the pediment reading Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, built this when consul for the third time; the main building as it stands today was begun by Hadrian circa 126 A.D.

The ‘sarcophagus’ was, in fact, a basin from the Baths. It was discovered in the fifteenth century, and was “admired not only for its artistic merit, but for the porphyry out of which it was made, and the great name with which it was associated.”1 After its discovery, the sarcophagus was placed first in the Piazza della Rotunda, and then under the portico, of the Pantheon in Rome. In the 1730s it was taken to San Giovanni in Laterano where it was installed in the Corsini Chapel, serving as the tomb of Pope Clement XII. After its discovery, the model was imitated in various forms from the fifteenth century onwards, from marble tombs for other clerics, to decorative objects like salt cellars, mantel ornaments, hob grates, and stools. However, a full size table following this prototype is extremely rare and only one other is known (see below).

The Tomb of Agrippa was recorded in Les Edifices antiques de Rome dessinés et mesurés tres exactement par Antoine Desgodetz, architecte in 1682 (figure 1). Desgodetz’s publication provided detailed engravings and accurate proportions of ancient Roman monuments to artists and architects in France and beyond. The architect George Marshall undertook the task of publishing the first English edition of the volume in 1771, which popularized the form in Britain. The sarcophagus is also included in Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s first work, Prima parte di Architettura e Prospettive (1743), where it is described as the sepulchral urn of Marco Agrippa made of porphyry “that today serves at the tomb of Clement XII,” and features in the Seconda parte de’tempi antichi, che contiene il celebre Pantheon by his son, Francsco, in 1790 (figure 2).

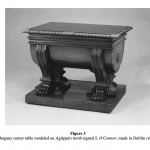

The only other known center table modeled on Agrippa’s tomb, today in a private collection, is illustrated in Irish Furniture, by Desmond Fitzgerald, 29th Knight of Glin, and James Peill. Signed S. O’Connor, it was made in Dublin circa 1775 and thus employs a concentrated scheme of Georgian ornament (figure 3). It is also of mahogany with a black marble top.

The present example dates from the early nineteenth century and adopts a more austere and linear design, eschewing extraneous ornament. The pared down approach to the table’s design chimes with the general tendency toward minimalism in France during the years following the Revolution and prior to the opulent flamboyance of the Empire style.

Aside from its provenance, having come from an old French collection, a further clue to its Gallic origin can be found on the reverse of the black marble top. A partial inscription in French indicates that the precious noir belge top was reworked from a much earlier commemoration tablet.

A further fascinating aspect of the table is the use of two contrasting woods; the trusses that hold the mahogany ‘basin’ section are, in fact, of maple wood. Oxidation and light fading has caused the color of the two timbers to merge, but when originally made, a clear contrast would have been apparent.

Such an erudite and sophisticated table would likely have graced a post-Revolution interior of great refinement.

Footnotes:

- Haskell, Francis, and Nicholas Penny. Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500-1900. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981. 47.

Comments are closed.