11491 A RARE PAIR OF EMBROIDERED SILK AND SILVER THREAD PICTURES DEPICTING AN EXQUISITELY CLAD BLACK LADY WITH SERVANT AND A CAMEL IN CEREMONIAL REGALIA LED BY A BLACK HANDLER Late Seventeenth or Early Eighteenth Century. Measurements: Picture with lady: Framed: Height: 24 1/4″ (61.6 cm); Width: 19 3/4″ (50.2 cm). Sight Size: 21 3/4″ […]

Research

Of moire white silk with colored silks and silver and gilded metal threads.

After the Renaissance, increased trade and the shift in emphasis of embroidery workmanship from the church to a more secular patronage brought a desire and taste for more sumptuous clothing and interior decorations. Continuing in the 17th century, needlework became richer as a result of “growing opportunities for luxurious living”1 and increased availability of finer materials such as colored silks and metallic thread.

Embroideries were produced by groups of people in diverse positions and stations. Schoolgirls completed needlework projects in the form of samplers and pictorial embroideries, items for the household were stitched by the mistresses of the household with the help of servants and included cushion covers, table covers and curtain panels, while professional male embroiderers produced pictures and clothing decoration.2

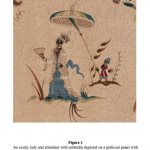

The present pictures depict scenes featuring non-European subjects within exotic landscapes. Cultural exchange and publication of illustrated travel accounts helped familiarize Europe with the costume of far-off lands, and “European textile designers [were inspired] to produced tapestries, woven silks, embroideries, and printed textiles that imitated imported fabrics or incorporated exotic motifs.”3 The dark complexion of the figures and the appearance of a camel suggests they represent a lady and servants of North African or Middle Eastern origin. The motif of a noblewoman attended with an umbrella appears in many exotic vignettes, for example, a circa 1690 British petticoat panel with chinoiserie designs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (figure 1). It was also highlighted as part of the embroiderer’s art in an engraving of La Tapissière by Nicolas de Larmessin the Elder in Les Costumes Grotesques et Les Metiers, circa 1685 (figure 2).

An interesting aspect of the woman’s ensemble are her red-heeled shoes. In 17th century Venice red chopines (high platform shoes) were favored by courtesans. This fashion practice of red heels, or talons rouge, was further popularized by King Louis XIV of France by the 1670s. They were dyed with an expensive pigment signifying status and were “restricted to nobles with the right genealogical qualifications to be presented at court,”4 but the style was imitated throughout Europe.

Footnotes:

1. Synge, Lanto. Art of Embroidery: History of Style and Technique. Woodbridge. England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2001. 110.

2. Epstein, Kathleen. British Embroidery: Curious Works from the Seventeenth Century. Williamsburg, Va: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1998.

3. Peck, Amelia, and Amy E. Bogansky. Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013, pp. 91-95.

4. Mansel, Philip. Dressed to Rule: Royal and Court Costume from Louis XIV to Elizabeth II. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005. 15.

Comments are closed.