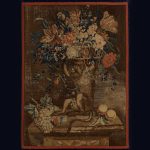

11056 A CHARMING REGÈNCE PERIOD TAPESTRY DEPICTING A MONKEY HOLDING A BASKET OF FLOWERS ALOFT Continental. First Quarter Of The Eighteenth Century. Measurements: Length: 36 1/2 ” (92.7 cm) Width: 27 1/4″ (69.2 cm)

Research

Of woven wool of various colors on a brown ground. The border old but later. Possible old strengthening of some colors.

Marks:

Bears shipping label:

Bill Reider Metropolitan Museum

Provenance:

Property from the Estate of Bill Reider, former curator of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

This tapestry represents the great European tradition of the use of the monkey as a decorative motif. Although popular during the first half of the eighteenth century in France, and giving rise to a genre of room decoration in its own right known as the singerie or Monkey-Trick, during the medieval period the monkey had been viewed negatively and associated with the devil. It was in the sixteenth century that Dutch and Flemish artists first noted the animal’s expressive potential. Pieter Brueghel the Elder (c. 1529-1569), a superbly naturalistic animal artist in the tradition of Albrect Dürer, painted a pair of monkeys in captivity in 1562 that seems remarkably sympathetic to their plight (figure 1). Like much of his art, it might have been an allegory relating to the Spanish occupation of his homeland. It was David Teniers the Younger (1610-1690) who first recognized the monkey’s humorous potential, and its possible use to satirize human beings. Teniers presented monkeys going about human daily activities such as playing cards, cooking, drinking and smoking, sometimes in human dress. Teniers’ monkey paintings enjoyed considerable popularity; it is said that Philip IV of Spain owned several and some remain in the Prado Museum today including one depicting a monkey sculptor.1

The monkey on the present tapestry is holding a basket with an elaborate display of flowers. This relates it to the Dutch and Flemish genre of still life, particularly the work of animal painters like Melchior d’Hondecoeter (1636-1695) who, although most famous as a painter of birds, also often included monkeys in his compositions (figure 2). Perhaps the tapestry is most similar to the work of the Flemish still-life artist Frans Snyders (1579-1657), who also showed monkeys behaving naturally, often stealing fruit and nuts from bowls and baskets, the rendering of the fruit, basket and monkey in the present tapestry are reminiscent of his work (figure 3). The appearance of the flowers borrows from the Dutch tradition of flower painting, especially the work of artists like Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder (1573-1621) and Jan Davidsz de Heem (1606-1684). Such still life paintings were imbued with symbolic meaning; Hondecoeter liked to show his monkeys next to peacocks, where the monkey represented unchecked appetite, and the peacock vanity. Flowers in Dutch art were a symbol of vanitas, intended to remind the viewer of the transitory nature of life. The juxtaposition of the monkey and flowers in the tapestry is interesting and unusual, and may be intended to remind the viewer of the folly of coveting transitory wealth and worldly goods.

The monkey also represented wealth and exoticism. The animal’s appeal was largely owing to its status as an unusual and foreign creature; there are no breeds endemic to Europe. Like many other symbols of the exotic, the fashion for the monkey was fed by growth in international trade and explains its special popularity in the Netherlands, who in the seventeenth century were building an extensive empire in the east. In France, the early popularity of the monkey is closely linked to the taste for chinoiserie or Chinese-inspired decoration. The oriental influence in the present tapestry can be inferred from its brown ground, which is similar to that used on the productions of the Soho tapestry works in London, which was operational in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries and managed by a craftsman of Dutch extraction, John Vanderbank. The brown grounds of these tapestries were considered to emulate oriental lacquer screens, the effect was referred to as “after the Indian manner.”2

The use of the monkey in decoration would be further developed in France by artists such as Jean Berain the Elder (1637-1711), who would include it in his elaborate decorative schemes or grotesques. It was Claude Audran III (1658-1734) who was the first artist to create the so-called “singerie” effect, placing monkeys in human clothing and depicting them decoratively in playful poses. Audran influenced the accepted master of the genre Christophe Huet (1700-1759) who created the greatest monument to the taste, the Grand Singerie at the Chateau de Chantilly in 1737. The popularity of this medium persisted, with Frederick the Great of Prussia commissioning Johann Christian Hoppenhaupt to create a singerie for his palace at Sanssoucci, especially prepared for the visit of Voltaire in 1750.

The present tapestry was previously the property of Bill Rieder, curator and administrator of the department of European Decorative Arts and Sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. He was a prolific writer on the decorative arts and furniture and was responsible for the redisplay of the English galleries at the museum. The tapestry was a longtime fixture on the wall of his office in the museum.

Footnotes:

- Nicole Garnier-Pelle et al., The Monkeys of Christophe Huet: Singeries in French Decorative Arts, Los Angeles, 2011, p. 18

- See, Edith Appleton Standen “English Tapestries ‘After the Indian Manner’.” in Metropolitan Museum Journal, Vol. 15 (1980)

Comments are closed.