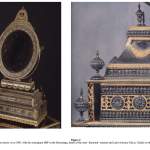

11357 A RARE POLISHED STEEL TABLE MIRROR WITH PIERCED ORB AND FACETED BALL UPRIGHTS SURMOUNTED BY ‘LUKOVICHNAYA GLAVA’ FINIALS Tula. Late Eighteenth Or Early Nineteenth Century. Measurements: Height: 11 3/4 ” (29.8 cm); Width: 10 3/4″ (27.3 cm); Depth: 3 3/8″ (8.5 cm).

Research

Of steel. The old but replaced mirror-glass, enclosed by a frame of cut and polished steel stylized rosettes, supported by pierced orb and faceted ball uprights surmounted by ‘lukovichnaya glava’ finials, on conforming trestle base. The reverse with replaced mahogany conforming arched panel.

Provenance:

New York Collection

This extraordinary dressing mirror makes extensive use of the distinctive faceted steel beads, often referred to as “diamonds,” which are the trademark of the decorative steel work produced by the celebrated Tula workshops in Russia during the eighteenth century. “Variously shaped…steel diamonds were distributed by the hundred on the surface of [an] object, where they created the allusion of glittering gems,”1 the present mirror possessing just such a jewel-like quality.

The mirror takes advantage of all manner of steel bead shapes—spherical, oval, oblong, pierced and cylindrical—that contributed to the unique decorative aesthetic created by the Tula craftsmen. It is differentiated from other known Tula items as the posts and stretcher employ hollow spheres, each formed of a system of oval faceted nuggets— a highly technical undertaking that would have challenged the skills of its maker to the limit.

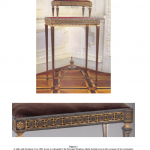

The distinctive rosettes framing the mirror glass are a particular recurring motif of the Tula workshops. They appear on a number of pieces supplied to Catherine the Great and other members of the Imperial family, for example, a table and footstool circa 1801 given to Alexander I by the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna on the occasion of his coronation (figure 1), as well as a toilet mirror circa 1801 in the Hermitage (figure 2). Like the present piece, the Hermitage mirror also employs ‘Lukovichnaya Glava,’ onion-dome finials, a characteristic feature in the architecture of Russian churches, the most famous of which is St. Basil’s Cathedral on Red Square in Moscow.

The craftsmen of Tula became renowned for their production of objects in steel following Peter the Great’s relocation of the Imperial State Armory to the town in 1712. The workshops of Tula began to manufacture domestic objects in steel soon after moving there. Tula craftsmen gained an international reputation for adapting the experience and techniques acquired in the creation of fine quality arms, and Tula is the only center known to have produced furniture made entirely of steel during the eighteenth century.2

The master craftsmen of the town worked either in the imperial workshops, from where they could also undertake their own commissions, or in private manufactories like the Demidov, Nikita Mosolov and Feodor Batashov workshops. Craftsmen such as those of the State Armory would have been among the few workmen experienced in working with steel given that, before the innovations of Henry Bessemer in the 1850s, the difficulty and expense of producing objects in steel largely precluded its manufacture in any great quantity. In consequence, the objects produced at the Tula workshops were highly prized.

The success of the Tula steelworks during the eighteenth century was based in large part on the patronage of Catherine the Great, who “took a great interest in this center of Russian arms manufacturing,”3 and purchased the objects that appealed to her when visiting the works. Objects in steel were also sent out as diplomatic gifts such as “lamps, caskets, inkhorns and even umbrellas, toilet services and mirrors.”4 During the second half of the eighteenth century Tula goods could also be bought by visitors and other craftsmen from an annual market that Catherine the Great herself attended, held each year on May 21st, not far from the royal residence at Tsarsköe Selo.5

Surviving accounts reveal that Tula wares were greatly admired by visitors to Russia. In 1755 Chevalier de Corberon wrote, “We went to dine at Count Potemkin’s. He showed us fine steel objects from Tula, which are of a rare beauty for the quality of steel, gilding and fine decoration”.6 Another Frenchman, the Comte de Ségur, ambassador to Russia from 1785, observed in his memoirs that, “Tula has been known for some time for its manufacture of arms… They also make works of art in steel and this branch of the industry is promoted by Catherine [the Great]… Her Majesty gave each one of us a present of a few pieces of the Tula manufacture, which were most finely worked.”7

Footnotes:

- Olausson, Magnus. Catherine the Great & Gustav III. Nationalmuseum, 9th October 1998-28th February 1999. Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, 1999.528.

- M. Malechenko, Art Objects in Steel by Tula Craftsmen, Leningrad, 1974, p5.

- Olausson, 526.

- Ibid., 527.

- Malechenko, p5.

- Chenenvière, Antoine. Russian Furniture, The Golden Age 1780-1840. London: 1988, p251.

- ibid., pp251-2.

Comments are closed.