9985 THE KING STANISLAS VASES AN IMPORTANT PAIR OF PAINTED AND GILDED, AND GILT FORGED IRON VASES FROM THE GATES OF PLACE STANISLAS, NANCY BY JEAN LAMOUR Nancy. Circa 1755. Measurements: Height: 53″ (134.6 cm) Width: 33 1/2″ (85.1 cm) Depth: 15″ (38 cm).

Research

Of painted forged iron with gilding and black paint below present and old decoration. Each vase flanked by the scrolling rocaille handles, the body with further applied gilt rocaille decoration, the whole raised on a similarly designed spreading base. A bouquet of various gilt flowers and foliage issuing from the mouth of each vase. Some local repairs to weather penetration. Painted decoration on one vase restored due to weathering. Old possible replacements to flowers. Rivets replaced by screws.

Provenance:

An Old Dallas, Texas Collection

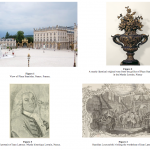

The present pair of vases comprised two out of the eight original models that crowned the wrought iron gates of four entrances to the Place Stanislas in Nancy, France (figure 1), now a World Heritage site, designed by the preeminent 18th century iron worker and designer Jean Lamour, and constructed between 1752 and 1755.

Another pair of vases from the original set on the gates of Place Stanislas is conserved today in the Musée Lorrain, Nancy (figure 2), which were deposited in the museum by the city on February 13, 1911.

In 1704, Stanislas Leszczyński (1677-1766) was elected King of Poland after the successful invasion of the country by Sweden, leading to his selection by Charles XII of Sweden to supersede Augustus II. However, he was forced to abdicate in 1710 when Augustus II was placed back on the Polish throne through the intervention of Russia and Austria. Stanislas refused to relinquish his title, however, creating the unusual situation whereby there were two kings of Poland. When Charles XII died, Stanislas sought refuge in Zweibrücken and then Alsace. In 1725 his daughter Maria became queen consort to Louis XV of France, and Stanislas resided at the Château de Chambord, along with his wife, Catherine Opalinska, until 1733.

The king of France supported his father-in-law’s claims to the Polish throne and, upon the death of Augustus in 1733, Stanislas traveled back to Poland in disguise and presented himself at the Convocation Diet in Warsaw where he was elected King of Poland once more. The victory was short-lived, however, when his reinstatement sparked the War of the Polish Succession. As a result of this conflict, Augustus III was placed on the Polish throne and Stanislas was given the Duchy of Lorraine and Bar as recompense, where he reigned from 1737 until his death in 1766.

It was as a result of this that Nancy was elevated to a residential capital city with its own princely court.

“As a ruler Stanislas was a model of the Enlightenment…an active protector of the arts and sciences and a patron of local talent.”1 He founded the Societé Royale des Sciences et Belles Lettres, established the first public library in Nancy, an oprhanage, hospitals, and free schools. In 1737 he initiated a series of building programs at his newly acquired ducal residences that would not only enhance his prestige as a benevolent sovereign, but were comprised of buildings that functioned for the benefit of the people. The aim was to connect the medieval Old Town of Nancy and the New Town begun under the Duke of Lorraine Charles III (1543-1608). Reconstruction projects in city were furthered by a later duke, Leopold Joseph (1679-1729), under the direction of Jules Hardouin Mansart, Germain Boffrand, and Boffrand’s pupil Emmanuel Héré de Corny (1705-1763). This meant that Stanislas already had a number of notable architects and artisans at his disposal upon his arrival when he initiated his building plans. We know little of Héré’s origins or training, but the Nancy-born architect was employed at the ducal office works prior to Stanislas’ arrival. In 1737 he was appointed governor of the royal Château de Lunéville, and “rapidly developed into an original and imaginative artist,”2 responsible for the church of Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours and the Hostel of the Royal Missions.

Stanislas selected Héré as court architect, who designed a large square and surrounding buildings with unified façades to harmonize with the pre-existing Hôtel de Ville, the seat of the city government. “The foundation stone of the first building in the square was officially laid in March 1752 and the royal square solemnly inaugurated in November 1755.”3 The Place Royale, as it was then called, was dedicated to Stanislas’ son-in-law, King Louis XV, with a statue of the monarch placed at its center. On the north end of the square, a triumphal arch connects Place Stanislas with the Place de la Carriere, a tree-lined promenade where jousting tournaments used to take place. This, in turn, links to the Place d’Alliance and the Palais du Gouvernement at the opposite end of this axis. Héré’s buildings on the Place Royale included the Opéra, the Musée des Beaux Arts, the Hôtel de la Reine, and the Pavillon Jacquet. It was Jean Lamour who linked these structures with his partially gilded wrought iron gates and lanterns on the four corners and west and east sides of the square, as well as the complementary staircase and balcony of the Hôtel de Ville. The result was a harmonious architectural ensemble, innovative in urban development. David Watkin offered the scheme high praise and particularly emphasized the ironworks: “The elements of variety and surprise, of enclosure and release, of contrasting building heights, and especially the curved openwork grilles of gilded wrought iron of Jean Lamour sheltering fountains in the corners of the Place Stanislas, create a Rococo liveliness in what is in essence one of the grandest pieces of formal Baroque town planning in Europe.”4

Jean Lamour (figure 3) was born on March 25, 1698, the son of a master locksmith in Nancy. He followed in his father’s footsteps as serrurier and taillandier (locksmith and tool maker), working in Metz until 1712, and then took two trips to Paris where he perfected his skills in metalwork and design. When his father died in 1719, Jean Lamour succeeded him in the post of locksmith to the city of Nancy. Before Stanislas had called upon him to contribute to the decoration of the square, Lamour was rarely employed in instances where the design aspect accounted for a major part of his professional work.5 However, his appointment as serrurier du roi in 1738 and subsequent commissions allowed Lamour to showcase his enormous talent and creativity, and solidified his reputation as the illustrious metalworker we know today.

In 1767 Jean Lamour published a discourse on the art of metalwork along with a collection of engravings of his designs for the square, which he dedicated to the recently-deceased king, entitled “Recueil des ouvrages en serrurerie que Stanislas le Bien-Faisant, roi de Pologne, duc de Lorraine et de Bar, a fait poser sur la Place royale de Nancy, à la gloire de Louis le Bien-Aimé…” The dedication page includes an illustration of Stanislas visiting Lamour’s ironworks during the production of the grilles for the square, which can be seen in the background (figure 4). The design for the gates that included the present pieces, which were described as “vases of isolated flowers,” appeared on Plate 8 of this book (figure 5). Gates of this style were placed on the southwest corner at the rue des Dominicains, the southeast corner leading to the Prefecture, the west side at rue Stanislas, and the east side at rue Sainte-Catherine. The northwest and northeast corners of the square are enclosed by more elaborate grilles surrounding the Fountains of Neptune (west) and Amphitrite (east), by Barthélemy Guibal, sculpteur et architecte ordinaire du roi.

It is likely that the vases were dismounted during one of several 19th century restoration projects. The first was attempted in 1864, the second in 1879, and a third renovation project of a larger scale in 1895, voted into action by the City Council of Nancy. According to an editorial in the L’Est Republicain on 5 February 1896, over sixty gilt wrought iron ornaments had been missing from the gates at that time.6 The vases until recently formed part of an old Dallas, Texas estate.

Footnotes:

- Coffin, Sarah. Rococo: The Continuing Curve, 1730-2008. New York, NY: Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, 2008. 92.

- Kalnein, Wend , and Wend . Kalnein. Architecture in France in the Eighteenth Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995. 93.

- “Place Stanislas, Place De La Carrière and Place D’Alliance in Nancy.” – UNESCO World Heritage Centre. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 Nov. 2014.

- Watkin, David. A History of Western Architecture. London: Laurence King, 2005. 322.

- Coffin, 95.

- Un Nancéien. “Tribune Publique: Les Grilles De La Place Stanislas.” L’Est Republicain [Nancy] 5 Feb. 1896, Troisième ed.: 2. Print.

Comments are closed.