9998 AN EXCEPTIONAL MUSICAL AUTOMATON CLOCK FEATURING A TURKISH TIGHTROPE WALKER AND FOUR MUSICIANS IN A GARDEN RAISED ON AN INLAID STAND IN THE TURQUERIE TASTE French. Second Quarter Of The Nineteenth Century. Measurements: Height: 28 1/3″ (72 cm) Width: 17″ (43 cm) Depth: 10 3/4″ (27 cm)

-

Figure 1

-

Figure 2

-

Figure 3

Research:

Of rosewood, boxwood, gilt-bronze and colored silks. The central figure of a tightrope walker surrounded by four musicians who move their heads and simulate playing instruments in an outdoor space with large tree, fence and draped curtain. The automaton scene under a glass dome resting on a base of Brazilian rosewood inlaid with inlaid satinwood decoration comprising an arcade of horseshoe arches with railing, centered by a clock face, above alternating feather and anthemion decoration surmounted by crescent moons. One small tree replaced. Clock movement: Eight-day striking movement with old replaced escapement. Musical Movement: Plays four tunes and is of Swiss manufacture, in excellent working order.

Marks:

Lever plaque engraved:

Ne dansez pas, danse a l’heure, dansez toujours

Provenance:

Duke de Béjar, Palacio de Orihuela.

Marqués de Argelita by descent.

Private collection, Valencia from 1967.

The present automaton clock contains as its main spectacle a remarkable mechanical group comprised of a Turkish acrobat and musicians, designed to imitate human movements, in this case on a miniature scale. It is all the more remarkable for the fact that the substantial base is beautifully inlaid with references to the Turkish world, and we know of no other examples of automata that incorporate this conceit.

France had a strong tradition for items made in the Turkish taste; Turquerie was very much in vogue during the ancien regime, the style informing both the fashion and art of the day. It underwent a further revival during the 1840s, the culmination of which can be viewed in a clock called Pendule ‘Turque à Musique’ designed by Léon Feuchère for Sèvres in 1843. The clock was completely adorned with Middle Eastern architectural motifs, arabesques, crescent moons, and Arabic writing, and was intended as a gift from King Louis-Philippe to the viceroy of Egypt.

The five figures of the present automaton each move independently of one another, and all have their own unique set of gestures. The mandolin player strums the instrument with his right hand while his head moves from side to side, and also nods up and down. The triangle player lifts his right arm up and down to strike the triangle, and his head nods up and down as well. The drummer lifts his right hand up and down to strike the drum and his head nods up and down, while the seated figure turns his head from side to side. Finally, the tightrope walker, as the central figure, features many movements. Firstly, he jumps up and down on the slackline; both of his legs bend at the hips and knees. His arms move up and down while holding his balancing pole, and he nods his head up and down.

The musical movement plays four tunes in turn, simultaneously with the actions of the figures. They can be set to play when the clock has struck, just after the hour, or activated at will. This action is controlled by a sliding lever: when in the left hand position, the automaton and music will start immediately and play continuously until run down; in the middle position the figures and music will play when activated by the clock movement; and in the right hand position the movements and music will stop instantly and remain locked in the off position until the lever is moved back to the middle or left. The automaton will perform twelve times when fully wound, while the musical movement will play fifteen times, until run down.

The French-made clock movement is an eight-day striking movement, which strikes the hours and half-hours on a gong mounted on the base, while the musical movement is certainly of Swiss manufacture due to its very high quality, although there are no markings.

The word automaton derives from the Greek automatos, meaning “acting of itself.” The production of automata reaches far back to Antiquity when simple principles of physics, such as air pressure and the movement of fluids, were applied to manipulate and propel objects. Ctesibus, an inventor and mathematician in 2nd century B.C. Alexandria devised the first hydraulic organ and water-powered automata. “Water entering a sealed compartment beneath a carved figure of a bird, for example, forced air in the compartment up through a tube inside the figure and across a sound hole to produce in the bird’s mouth something like a whistle.”1

In the 14th century we see the appearance of “jaquemarts” (also known as jacks-of-the-clock), which were human figures holding hammers that pivoted to ring the bells of weight-powered tower clocks. In the Renaissance, the incorporation of the spring into clocks and watches led to the invention of wind-up toys. “Around 1730, one of the many clockmakers of the Black Forest in southwestern Germany…had the idea of marking time’s progress with a mechanical cuckoo, in which he was much imitated.”2

As automata evolved, they became increasingly complex, and more closely resembled the animals and humans they emulated. In many cases the clock-making component was altogether abandoned. “When automaton-builders began to make mechanical imitations of skilled human beings, they were simultaneously demonstrating their own supreme technical skills as mechanicians and parodying the technical skill of those professionals whom their machines imitated.”3 One of the first and most talented of these mechanicians was the French inventor Jacques de Vaucanson (1709-1782). Born the poor son of a glove-maker, Vaucanson first followed a course of religious studies under the Jesuits. However, after an encounter with the surgeon Le Cat, he developed a keen interest in anatomy and began to develop mechanical devices that imitated biological vital functions such as respiration, circulation, and digestion.

In 1738 he exhibited three life-size automata in Paris to the amazement of its citizens (figure 1): Le Flûteur (the flute player), Le Canard (the duck), and Le Tambourinaire (the drummer). Based on an Antoine Coysevox marble sculpture of a faun in the Tuileries Garden, the Flûteur was carved in wood with a complicated interior system of “axles, cords, pulleys, lever, chains, bellows, pipes and valves.”4 When operated, the faun’s fingers would move up and down over the holes of his flute, the tongue would move, and the lips would open and close allowing air to emit from its mouth at varying intensities. Vaucanson had “perfectly harmonized” all of these movements so that the faun could play entire pieces of music. The Canard was equally impressive and, when activated, could turn its neck and head, flap its wings, and quack. It had the added feature of drinking water and eating seed, which, through a series of rubber tubes inside its body, was then “digested” and realistically expelled.

Another famous automaton builder was Pierre Jaquet-Droz, son of a Swiss watchmaker in Neuchâtel who sold elaborate clocks to the likes of King Ferdinand of Spain, the most extravagant of which also included an automaton of a shepherd playing a flute. By 1773 Pierre and his son Henri-Louis conceived three androids, or life-size automaton in the form of human beings that performed human functions. They were the Designateur (Draughtsman), the Musicienne (Musician) and, most famously, the Écrivain (Writer). Comprised of over 6,000 parts, the Écrivain could be programmed to write any message up to forty characters in length. He dipped his pen in an inkwell, shook off the excess, and precisely completed his message while his eyes either followed the pen or looked around him. This display surely inspired another mechanical masterpiece of 1784, the Joueuse de Tympanon, or “The Dulcimer Player.” Constructed by Pierre Kintzing and David Roentgen for Queen Marie-Antoinette, this lavishly costumed two-foot tall musician accurately played eight individual songs on the dulcimer, and is today in the Musée des Arts et Métiers.

In the late 18th and early 19th century a number of mechanicians rose to fame including Wolfgang von Kempelen (1734-1804), whose masterpiece, “The Turk,” was a life-size chess player (although this was later found to be partially operated by a human), and Johann Nepomuk Maelzel (1772-1838) who created the Panharmonicon, an ensemble comprised of forty-odd musicians playing a variety of instruments. In 1818 Maelzel added an automaton slackline acrobat to his repertoire. According to a contemporary authority in a treatise on organ building “the most surprising thing about this little masterpiece of mechanics is the impossibility of figuring out how all of its various movements can be produced, because the automaton suspends itself now by one hand, now by the other, now by its knees, now by its toes, then it straddles the rope and twirls its body around it, thus abandoning one by one all of its points of contact with the rope, through which it must necessarily pass whatever communicates movement to it.”5

In the 19th century Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin (1805-1871) made a name for himself as a clockmaker, inventor, and illusionist. The son of a talented watchmaker, Robert-Houdin abandoned his studies of law to follow in his father’s footsteps. According to his autobiography, Confidences et revelations (1858), in the 1820’s he ordered a set of books on clock-making, but a mix-up by the bookseller resulted in Robert-Houdin receiving a set of books about magic, which he nevertheless kept and practiced enthusiastically.6 He simultaneously pursued careers in horology and conjuring, combining the two to devise mechanical tricks. In the 1830s and 1840s Robert-Houdin devoted much of his time and energy to his many impressive inventions and automata, which were often incorporated into his magic shows, most notably his Soirées Fantastiques, which premiered at the Palais Royale in 1845. These included a blossoming orange tree, a cups-and-ball manipulator, and trapeze artist. Even after his retirement, Robert-Houdin continued to work with automata; in 1866, for example, he was called upon by the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers to repair Kintzing and Roentgen’s Joueuse de Tympanon.7

In France, the construction of automata reached its apogee in the mid-1800s “during the lush days of the second empire under Napoleon II and Eugénie, before the Franco-Prussian War, and into the Bell Époque.”8 Unlike the examples of the previous century, which were made for public and private exhibition, this new era of automata were also made for personal enjoyment in the homes of the aristocracy and wealthy merchants. Automaton clocks were retailed by Parisian marchand-merciers specializing in luxury objects. In the case of the present piece, the firm most likely responsible was La Maison Alphonse Giroux, also known as “Giroux & Cie.,” founded in 1799 by François-Simon-Alphonse Giroux and established on the rue du Coq Saint Honoré in Paris. The shop dealt in objets de curiosité, fine art, and dolls, as well as “ornate objets d’art and technically sophisticated furniture,”9 and their clientele included several members of the French Royal Family including Louis XVIII, Charles X, and Napoleon III. In 1838 François-Simon’s eldest son, Alphose Gustave succeeded as head of the firm. He was “fascinated with mechanics and new technology”10 and in “[pursuing] his dream of showing ‘everything that Parisian fashion and industry had to offer’,”11 presented to the public a writing and drawing android by Houdin in 1843. An album produced by the firm enitled ‘Meubles et Fantasies’ included watercolor drawings of other automata, including a cage of birds and a magician very similar to extant examples by Houdin on inlaid wood bases sold by the firm.

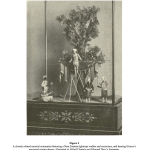

A musical automaton closely related to the present piece featuring a Near Eastern tightrope walker and musicians, and bearing Giroux’s engraved copper plaque, is in the collection of M. Charliat and illustrated in Alfred Chapuis and Edmond Droz’s Automata: A Historical and Technical Study (figure 2).12 A further example, circa 1837, attributed to Houdin and possibly retailed by Giroux, was sold by Sotheby’s New York, 20 October 2009 (figure 3). Each of these possess a similar layout of a central figure on a tightrope with one or two musicians to each side, positioned in front of a draped curtain before a large tree. In addition, both the Charliat and Sotheby’s examples have the additional shared feature with the present automaton of a foliate marquetry inlaid base.

Footnotes:

1. Metzner, Paul. Crescendo of the Virtuoso: Spectacle, Skill and Self-Promotion in Paris During the Age of Revolution. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1998. 162.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid., 160.

4. Ibid., 163.

5. Ibid., 186.

6. Ibid., 192.

7. Ibid., 208

8. Guinness, Murtogh D. The Murtogh Guinness Collection. New York: The Collection, 1982. 26.

9. http://urbanchateau.com/library/articles/giroux

10. Ibid.

11. Muchembled, Robert, and E W. Monter. Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.161.

12. Chapuis, Alfred, and Edmond Droz. Automata: A Historical and Technological Study. Neuchâtel: Éditions du Griffon, 1958. 262, fig. 319.

Comments are closed.