9566 A FINE & UNUSUAL LATE NEOCLASSICAL MAHOGANY SECRETAIRE COMMODE RETAINING ITS ORIGINAL ÄLVDALEN PORPHYRY TOP Stockholm. Circa 1795. Measurements: Height: 34 5/8″ (88 cm) Width: 45 1/2″ (115.6 cm) Depth: 23 1/2″ (59.7 cm)

Research

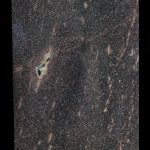

Of mahogany with gilt bronze mounts. The rectangular Älvdalen porphyry top above a vertically fluted narrow frieze, below which are four paneled graduated drawers each mounted with a finely cast oval spiral motif gilt bronze drop handle. The top drawer concealing a finely fitted secretaire. The four corners defined by fluted columns with turned plain capitals. The whole resting on four unusual carved acanthine feet, each ending in a gilt bronze collar.

In the mid-18th century, a reaction against the florid decoration of the Rococo style in France led to a Graeco-Roman classicism expressed in symmetry, straight lines and columns, Greek key patterns and other antique motifs. This neoclassical style was promoted in Sweden by Gustav III, whose admiration for life at the French court of Versailles resulted in elegant, delicate interpretations of decorative art objects. Gustav III had been studying in France when, in 1771, he learned of his father’s death, and returned to Sweden with drawings, models, and objets d’art that reflected the new, restrained fashion.

Swedish architects of the era also visited France and Italy, and the Gustavian style they created upon returning was considerably influenced by the French “Gôut grec.” In addition, French artists and craftsmen emigrated to work and teach in Sweden.1

Gustav III made a return journey to Paris and also Rome in 1783-84, after which a “purer and stricter”2 form of Neoclassicism evolved. What became known as the ‘Late Gustavian style’ developed to incorporate a wider variety of designs and materials “Mahogany, a new and exotic wood, was dominant; it was often used for secretaries, commodes and desks, with simple brass moldings around the drawers…”3

The commode retains its original Älvdalen porphyry top. The quarry was discovered in the Älvdalen valley in 1731 but it was not until 1788 that serious mining workshops were established. A fire in the late 1860s greatly limited production and “because of its rarity Swedish porphyry was treasured throughout Europe during the 19th century, and as a national export an symbol of pride in Sweden, it enjoyed high status at home as well.”4 The speckled appearance of the table top bears uncanny similarities to photos of galaxies taken from deep space.

Although loosely inspired by severe late 18th century French classicism, this commode is unusual in having fully freestanding corner columns and original mercury gilded handles with fan relief decoration, which are more in line with English prototypes of the period. The finely carved acanthine feet are also most uncommon and cleverly incorporate an element of sculptural detail which alleviates the otherwise strict geometry of the commode. This departure from the formulaic indicates a special commission and, given the beautifully drawn proportions of the piece, it is likely that it was designed by an architect.

A further distinctive feature is the extensive use of runs of carved fluting to the drawer divisions and under the top. Such a detail can be found on a bureau by the renowned ébéniste, Gottlieb Iwersson, illustrated in Sigurd Wallin’s Nordiska Museets Mobler Fran Sevenska Herremanshe. Vol. III, Plat 862 (1931). Furthermore, it is interesting to observe the shared Anglo-Gallic influences of these two pieces (figure 1).

Footnotes:

- Groth, Ha åkan, and Fritz . Schulenberg. Neo-classicism in the North: Swedish Furniture and Interiors, 1770-1850. London: Thames and Hudson, 1990. 9.

- Ibid., 10.

- Ibid., 11.

- Koeppe, Wolfram, Anna M. Giusti, and Luchinat C. Acidini. Art of the Royal Court: Treasures in Pietre Dure from the Palaces of Europe. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008. 348.

Comments are closed.