8054 AN EXQUISITE MAHOGANY AND KINGWOOD SECRETAIRE CABINET OF SMALL PROPORTIONS POSSIBLY BY MAYHEW AND INCE English. Circa 1770. Measurements: Height: 85″ (216 cm) Width: 34″ (86 cm) Depth with bureau closed: 21 1/2″ (54.5 cm) Depth with bureau open: 37 1/4″ (94.5 cm).

Research

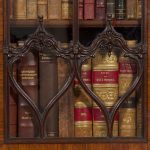

Of mahogany, kingwood, boxwood and ebony with giltbrass original handles. The molded cornice with interrupted dentilled frieze above covetto molding above a frieze with inlaid fluting set with stylized flowerhead patera. There is a shadow mark of approximately 5” and two old screw fix points to the center of the top of the cornice, which could indicate some form of plaque or small up stand, presumably later added, then removed. The frieze above two doors opening to a shelved interior, with inlaid borders and ebony stringing set with shaped glazing bars with inverted arches surmounted by scrolling decoration to the base supporting uprights in the form of a column and half columns to the side from which springs a frieze of gothic arches issuing below hanging harebell garlands. The projecting base with geometric inlay to the top above five graduated drawers, each with graduated geometric inlay with paired gilt stylised foliate drop handles, the upper pair of drawers combined and opening as a bureau with drawers to the rear, the remaining drawers raised above a molded edge on a plain plinth base.

Provenance:

A private collection, Kent, UK

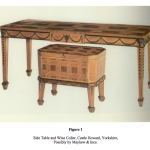

The present elegantly proportioned and finely detailed cabinet is a superb and unusual example of the English bureau secretaire of the second half eighteenth century. The sophistication of the design and execution of the cabinet suggests that it must have been produced by one of the leading cabinet makers of the day. The design of the piece has a number of affinities with the work of the celebrated firm of Mayhew and Ince; the unusual geometric inlay to the lower section also has parallels with pieces associated with the firm at Castle Howard, Yorkshire (figure 1), as well as with furniture by James Cullen commissioned for Hopetoun House, West Lothian.

The design of the glazing bars to the upper section of the bookcase represents a highly original and inventive combination of a number of different styles. In the bottom section of the doors, gothic ogee arches, terminating in acanthus leaves, lead into delicate scrolls of rococo decoration centred on the motif of a classical palmette, itself surmounted by a pagoda-esque arch of stylised foliate form. Elegant, classically derived, columns spring from bosses carrying guilloche decoration, set amongst this carving, rising to a frieze of gothic arches from which issue classical harebell garlands. The paired dentils to the cornice also represent a highly unusual interpretation of a classical architectural device.

The pointed arches give the design of the glazing bars an accent that is chiefly gothic but mixed with the classical and the rococo with a trace of Chinese forms. The variety of these influences, the confidence with which they are combined and the mastery of their execution suggests a designer of considerable sophistication and accomplishment. We know that one such designer to work in this manner of combined influences was William Ince of the firm of Mayhew and Ince, cabinetmakers to the English aristocracy. That company’s Universal System of 1762 features plates designed “in the rococo convention with a considerable admixture of the Gothic and Chinese.”1

The imaginative combination of styles characterised some parts of the furniture design of the second half of the century. Cabinets designed in the Chinese taste by Chippendale and his contemporaries frequently feature touches of rococo decoration, with Oriental motifs applied to conventional European forms.2 However, this particular combination of such a variety of styles, distinguishes Mayhew and Ince’s work from that of their contemporaries and from Chippendale’s Director (first published in 1754 but appearing in subsequent editions up to 1762), to which it was heavily indebted in conception and content. In the words of the furniture historian Ward-Jackson: “The style of the designs is likewise influenced by the Director, but they possess certain characteristics of their own, the most marked being the frequent use of elaborate symmetrical patterns, half Gothic and half rococo, executed in fretwork and applied blind to panels or used as an openwork filling for a frame.”3

We know that Mayhew and Ince did employ the form of the gothic arch in glazing bars from a mahogany china cabinet bearing the trade label of the firm, today in the Museum of Decorative Arts, Copenhagen. The doors of that piece feature a delicate framework of gracefully curved ogee arches carved with finely worked scrolls.4 The cabinet can be dated to about 1760 and is somewhat related to the designs for bookcases in recesses that appeared in plate 19 of the Universal System.5

The present secretaire is further distinguished by the use of contrasting inlaid woods to great decorative effect. This is apparent in the surface of the projecting lower section and in the drawer fronts, where a highly unsual geometric patterning enlivens the surface, the design expanding to fill each of the graduated drawers. The use of such radical geometric ideas is rare on English furniture of this period, however a precedent is to be found on an unusual side table and wine cooler associated with Mayhew and Ince at Castle Howard, Yorkshire,6 as well as a remarkable pair of commodes supplied by James Cullen to the Marquess of Linlithgow at Hopetoun House.7

The Castle Howard pieces display a marquetry pattern of intersecting octagons in contrasting woods comparable to the decoration on the present piece, which lead the historian Gervase Jackson-Stops to speculate on a continental influence in their design. But the use of dark neoclassical swags on a lighter wood is characteristic of Mayhew and Ince’s work and they are one of the few firms known to have supplied furniture to Castle Howard. Similarly James Cullen juxtaposed adjacent inlaid bands and lines of contrasting woods, creating geometric effects with the grains of the woods. While the Hopetoun commodes are distinguished by the bold use of massive inlaid x-shapes to the front and sides, the graduating geometric pattern to the drawers of the secretaire is in its way a comparably daring and radical decorative solution.

We are grateful to Simon Redburn for his help in compiling this description.

Footnotes:

1. Ralph Edwards ed., The Shorter Dictionary of English Furniture, 1983 ed., p. 663.

2. Ralph Edwards ed., The Dictionary of English Furniture, Volume I, 1990 edition, p. 185.

3. Quoted in Anthony Coleridge, Chippendale Furniture: The Work of Thomas Chippendale and his Contemporaries in the Rococo Style (1968), p. 65.

4. Ralph Edwards ed., The Dictionary of English Furniture, Volume I, 1990 edition, p. 191, Fig. 54.

5. Quoted in Anthony Coleridge, Chippendale Furniture: The Work of Thomas Chippendale and his Contemporaries in the Rococo Style (1968), p. 67.

6. Gervase Jackson-Stops (rd.), The Treasure Houses of Britain: Five Hundred Years of Private Patronage and Art Collecting, New Haven & London, 1985, p344.

7. Anthony Coleridge, Chippendale Furniture: The Work of Thomas Chippendale and his Contemporaries in the Rococo Style (1968), pl. 416.

Comments are closed.