7013 AN IMPORTANT AUBUSSON CARPET TO A DESIGN BY EUGENE VIOLLET-LE-DUC FOR THE CATHEDRAL OF NÔTRE DAME DE PARIS French. Circa 1860. Measurements: Length: 20′ (6 m) Width: 15′ (4.59m)

-

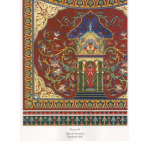

Figure 1

-

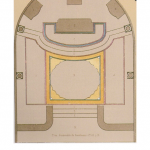

Figure 2

-

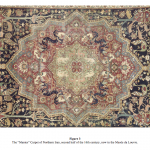

Figure 3

-

Figure 4

Research

Of flat woven wool. The whole centered by a temple of Islamic design issuing a profusion of stylized foliate tendrils against a red ground and edged with a border decorated with a repeat acanthus pattern.

The design of the present carpet was the work of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879) for the sanctuary of Notre Dame de Paris in the 1860s.

Viollet-le-Duc was a highly talented and individualistic architect and designer, as well as being an eminent art historian. Despite an early passion for architecture, he refused to enter the École des Beaux-Arts, choosing instead the experience of working with practicing architects and traveling France and Italy to view great works from the past. Viollet-le-Duc was part of an international group of theorists who imbued ornament with a new importance and his Entretiens sur l’architecture (1858) was cited by Victor Horta and Gaudí as an influence on their theories of architecture.

Although he was generally hailed in his time, Viollet-le-Duc did have his detractors, such as the sculptor August Rodin, who felt his artistic interventions too extreme. Nevertheless, his accomplishment and subsequent fame led to his most notable other commissions, for the rebuilding and furnishing of the Imperial residence of Château de Pierrefonds (1857–70) for Napoleon III, and for the restoration of Château d’Eu for the Orléans family (1862-79).1

Numbered among France’s most important nineteenth century architects, Viollet-le-Duc was one of the leading exponents of medieval architecture. He rejected the ad-hoc and often fantastical reconstruction of the traditional approach to the restoration of medieval buildings, stating in his renowned Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture that “To restore a building is not to repair or rebuild it, but to re-establish its original state.”2 To this end he undertook a series of commissions to work on some of France’s most magnificent medieval buildings, exactingly reconstructing them in their entirety, including furnishing the interiors.

As a leading member of the Conseil des Bâtiments Civils, Viollet-le-Duc won the prestigious assignment to restore the cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris from the Commission des Monuments Historiques in 1845, a project that lasted until the end of his life. His plans, drawings and sketches for the project were reproduced in his 1868 publication, Chapelles de Notre Dame de Paris: Peintures murales executées sur les cartons de E. Viollet-Le-Duc … relevées par Maurice Ouradou. It is this work which includes the design for the present carpet, illustrated in Plate 59 (figure 1).

Two carpets were produced to this design, the present piece and one which had formerly been laid out in the sanctuary of Notre Dame de Paris and today remains in possession of the cathedral. Importantly, both the Notre Dame carpet and the present example are of identical dimensions. They differ only in that the top of the Notre Dame carpet is curved to accommodate the steps of the altar, which can be seen in Plate 60 of Chapelles de Notre Dame de Paris (figure 2), whereas the top of the present carpet straight. Apart from this aspect, which affects one of the outer borders, the entire complex design of the body of the carpets is identical in both.

Additionally, Viollet-le-Duc also created a carpet of complementary design to cover the stairs leading to altar for Notre Dame de Paris, which is embroidered with the name of its maker, FREDERIC TIXIER / Fbt DE TAPIS À AUBUSSON.

The general layout of the design, being in landscape format with a central subject surrounded by a scalloped oval shape, as well as the color scheme of green and beige tones combined with deep red, are closely related to the famous “Mantes” Carpet of Northern Iran, today in the Musée du Louvre. It dates from the second half of the 16th century and was formerly the property of the church of Notre-Dame in Mantes, which was documented by Viollet-le-Duc in 1872 (figure 3).

While the palette of the present design evokes medieval times, the stylized meandering foliage, also found in the decoration at Pierrefonds, constitutes a radically different interpretation of these ancient patterns, and has been described as “an important preliminary step towards Art Nouveau.”3

The distinctive, delicate foliate scrolls, which issue from and surround a representation of an Islamic structure at the center, are repeated in many of Viollet-le-Duc’s most acclaimed works. Professor Martin Bressani, the leading authority on Viollet-le-Duc, has commented that this motif is one of the architect’s trademarks and “it is hard to imagine anyone else having designed [the carpet].” The curving, elongated lotus leaves and flowers entwined around the central element in the present carpet are also found in decoration designed by Viollet-le-Duc for the Chapelle de la St Enfance at Notre-Dame4 (figure 4).

Similar motifs by Viollet-le-Duc appear on a grille in the Salon des Guise at the Château d’Eu and on the domed ceiling of the Chambre de l’Impératrice at Château de Pierrefonds, commissioned by Napoleon III.5 The warm tones of the present carpet are also comparable with the colors used by the architect at Pierrefonds. Recalling the rich hues of the medieval world, the walls of the great hall are paneled in red and ochre, which are also the principal colors of the present carpet. The same colors could also be found in Napoleon III’s bedroom.6

The central design of the carpet is most likely based on the design of an ablution fountain situated in the heart of the court yard of some Islamic mosques. Professor Nasser Rabbat of The Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at MIT kindly pointed out a likely source of inspiration for Le Duc, when drawing the central theme for the present carpet. Professor Rabbat explained that “Viollet-le-Duc was indeed very much familiar with Islamic architecture. He knew and read the work of two architects and art historians who traveled to and worked in Egypt: Pascal Coste who published a major book, Architecture Arabe ou Monuments du Caire and Jules Bourgeoin who wrote L’art Arabe.” Professor Rabbat suggests that “Le Duc might have seen similar a pavilion in the illustrations of Coste’s book, which he owned […] he even wrote about Coste in his own book.” Indeed, imagery from numerous plates within this publication reverberates throughout the details of the carpet, such as the shaped finial on top of the domed monument, its horseshoe arches and the exotic palms and vegetation growing on top of and through the structure.

1 Macmillan Dictionary of Art, London, Macmillan, 1996, p. 596.

2 Dessins inédits de Viollet-le-Duc, Paris, Commission des Monuments Historiques, 1894, p. 47.

3 A3 with chateau d’eu

4 A. Kroll, Historic Houses, London, Collins, 1969, p. 69.

5 A. Kroll, Historic Houses, London, Collins, 1969, p. 69.

6 Macmillan Dictionary of Art, London, Macmillan, 1996, p. 594, 595 598.

Comments are closed.